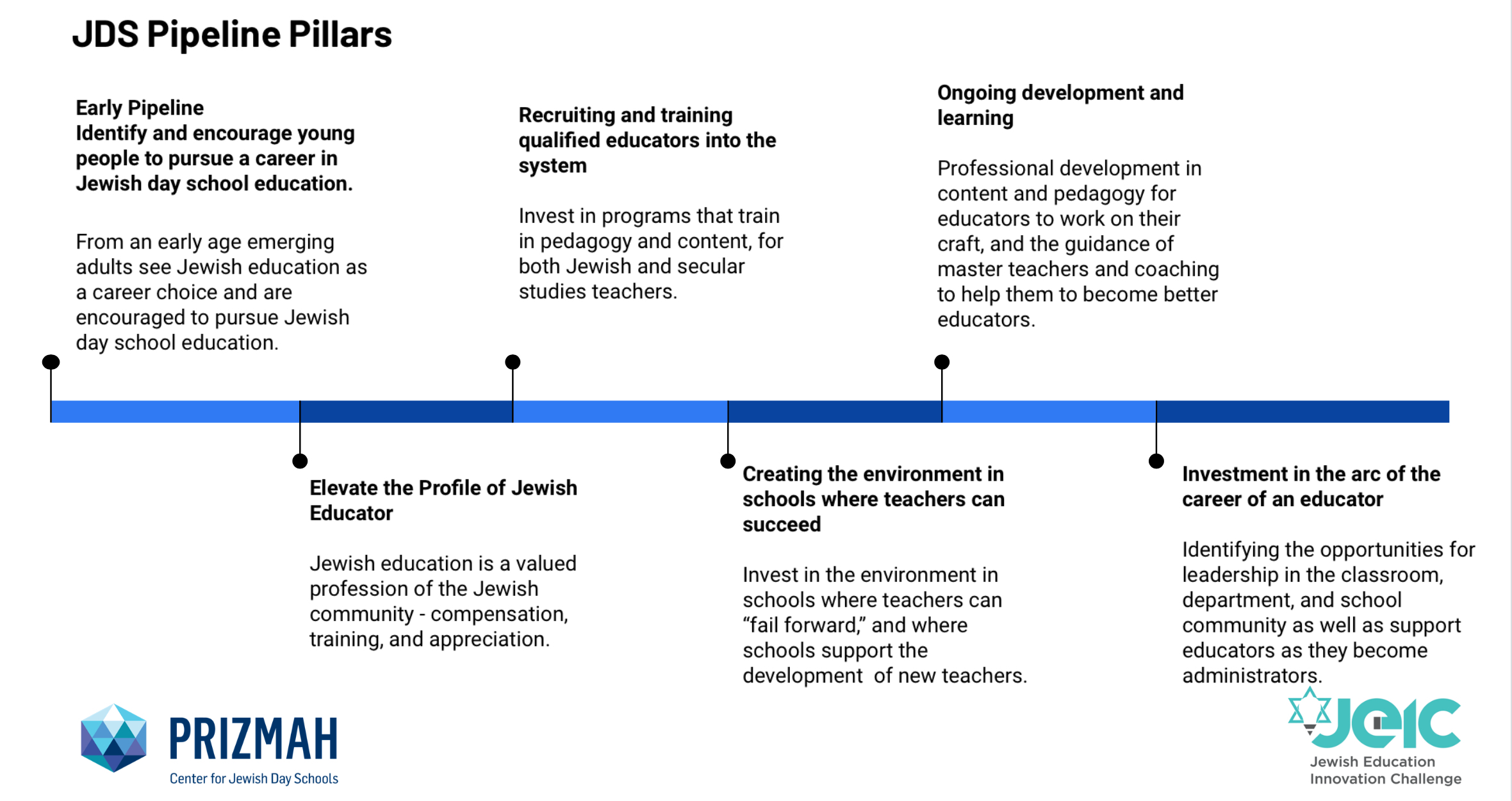

Almost three years ago, I was tasked by Yeshiva University to research and develop proposals for how to encourage more students to pursue careers in Jewish education in North American Jewish day schools. When speaking to leaders in the field, I often heard a similar hypothesis about why fewer young men and women were choosing to become teachers. There were two key factors: the rising cost of living in Jewish communities, combined with teacher salaries that have not kept pace; and the generally negative communal attitude towards teachers and the teaching profession.

If indeed these were the two primary factors, I wondered if much could be done to tackle them by simply working with college and graduate students. How could we possibly make a difference without large-scale community-facing initiatives to tackle day school affordability, teachers’ salaries, and the way parents, boards and teachers interacted?

Focus groups and individual conversations with young men and women during that research phase pointed in a different direction. Students often wondered how they could “make it work” as Jewish educators, but they also expressed a passion and desire to make a difference. Inspired by their own teachers or personal experiences in informal settings, these students expressed a desire to share their passion for Torah learning with others and pursue careers where they can feel they are living and passing on their values on a regular basis. Yes, work needs to be done to tackle broader communal issues, the inhibitors that may hold people back from (to borrow language from the 2019 CASJE study), but that did not mean that parallel work could not also be done to increase the stimuli and self-awareness that bring them into the field.

Over the past two years, the work of the Chinuch Incubator at Yeshiva University has reinforced this theory. Established by RIETS (YU’s rabbinical school) and the Azrieli Graduate School of Jewish Education, the Chinuch Incubator seeks to identify, inspire, prepare and support young men and women as they consider careers in Jewish education. How do we do this?

Identify and Inspire

In individual conversations with undergraduates, many have pointed to either specific shiurim they attended or personal conversations they had that inspired them to consider a career in teaching. Someone either noticed their talent and encouraged them to explore further, or ideas they heard pushed them to consider the possibility of teaching more seriously. Educators must proactively look for opportunities to unabashedly share with older students what they love about their work and encourage those that demonstrate potential to consider whether it is for them.

Inspire and Prepare

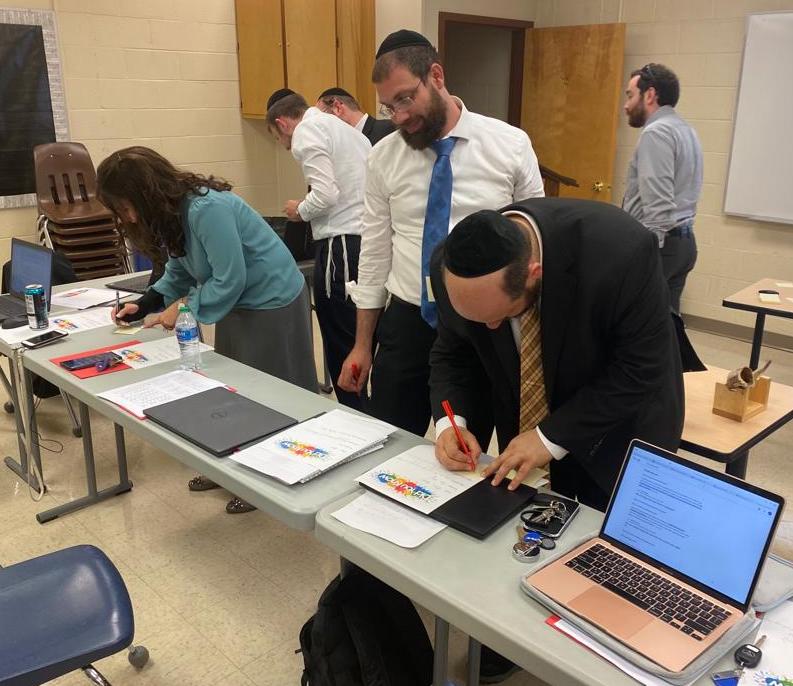

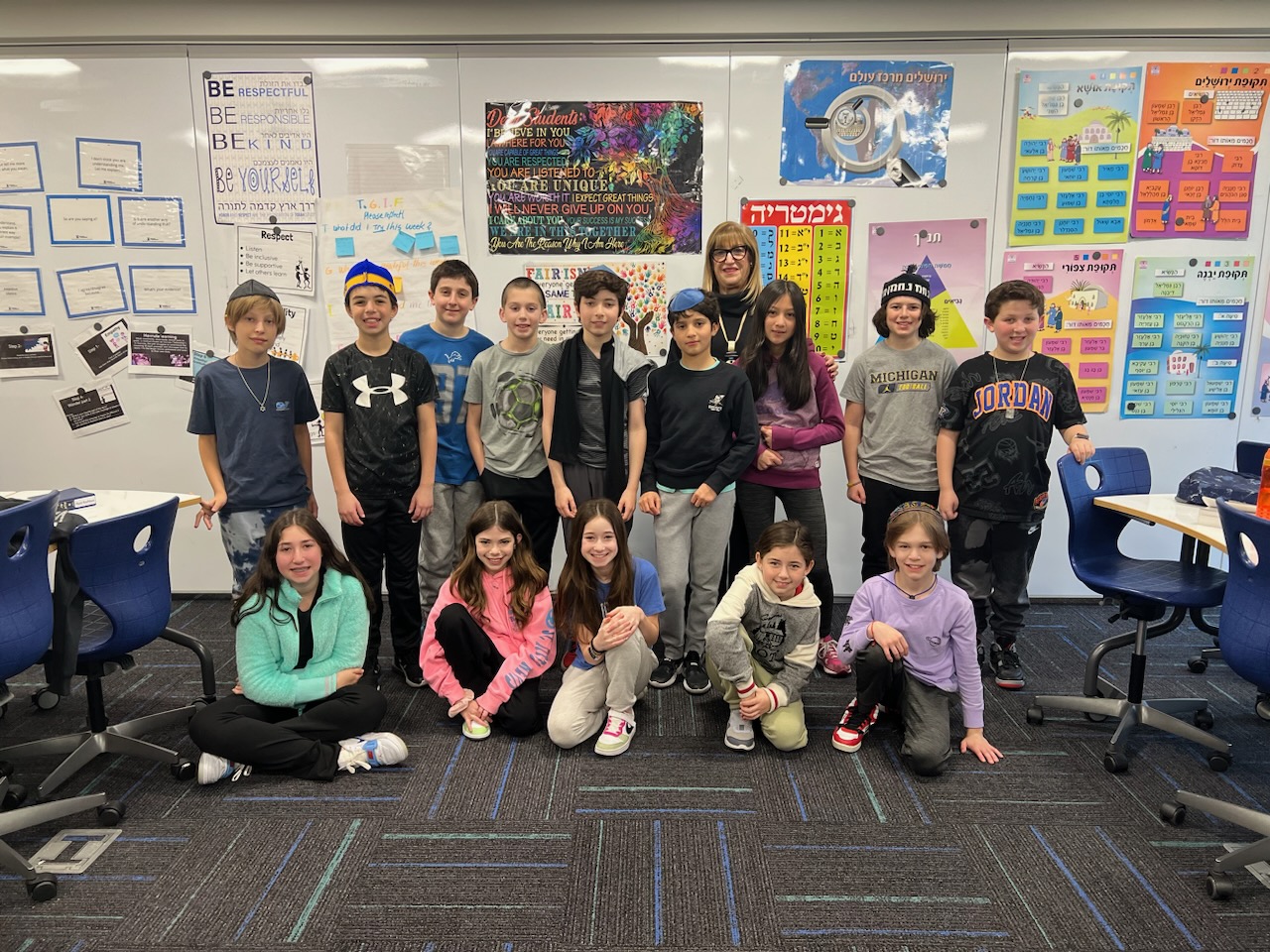

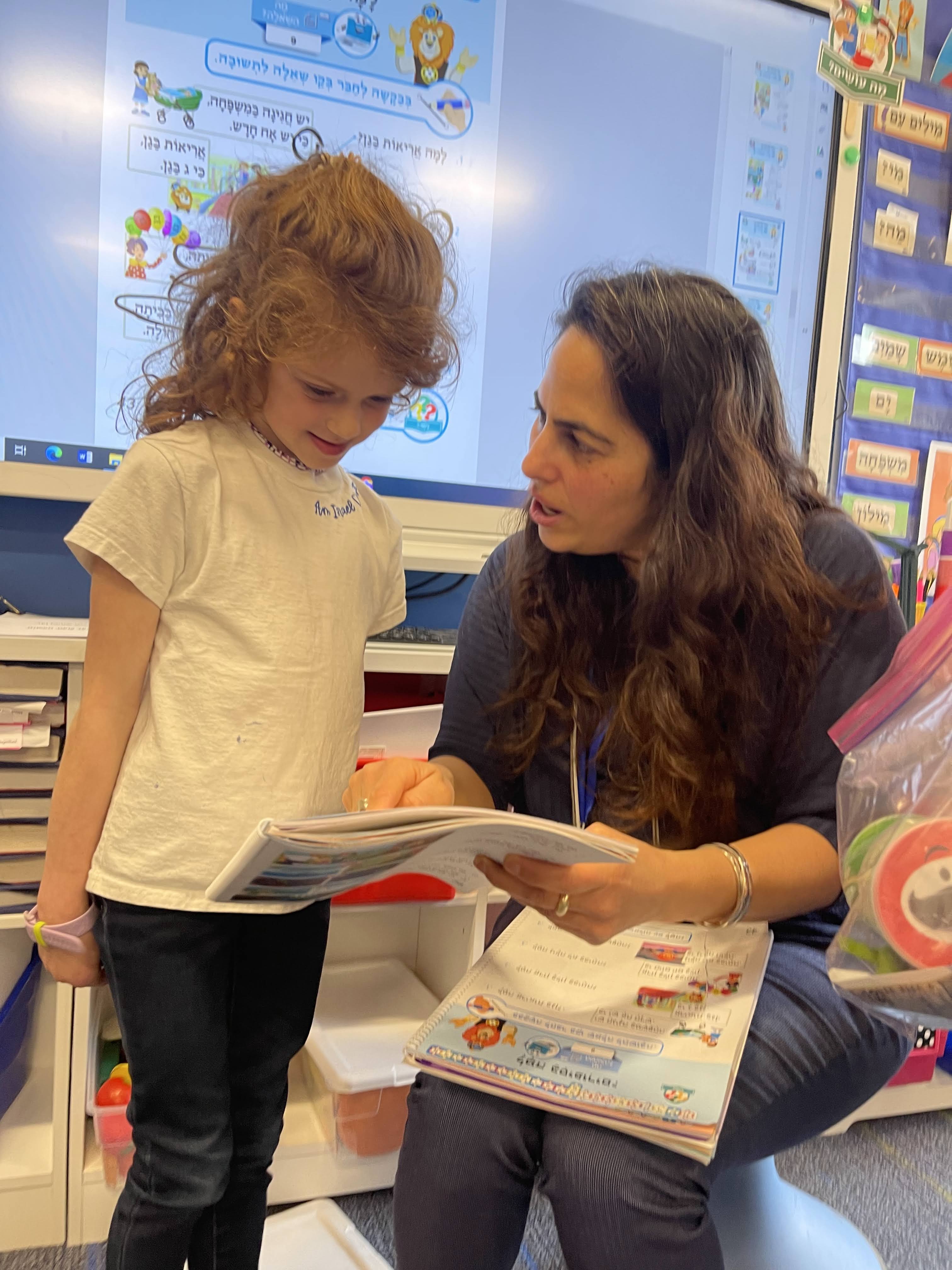

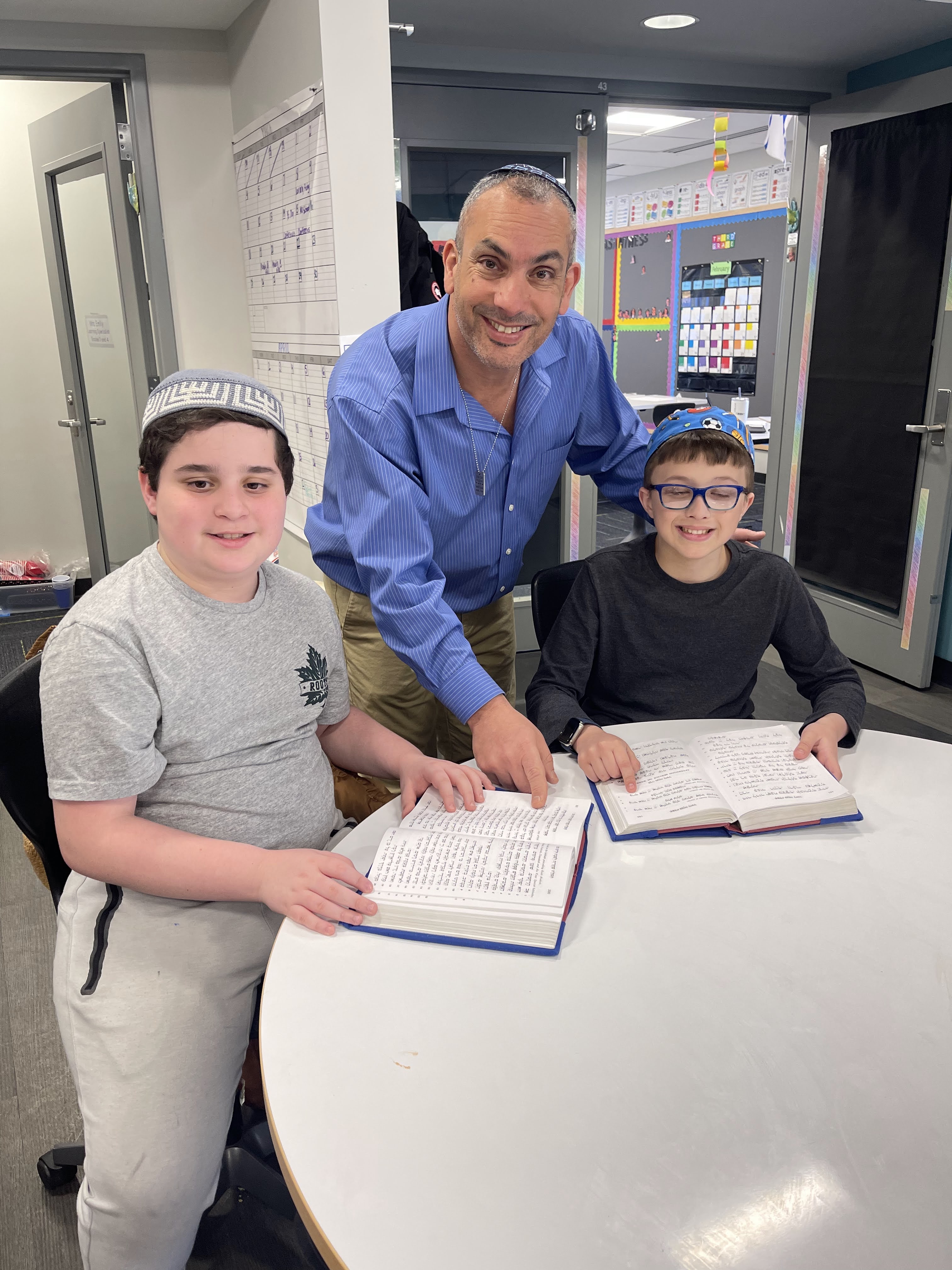

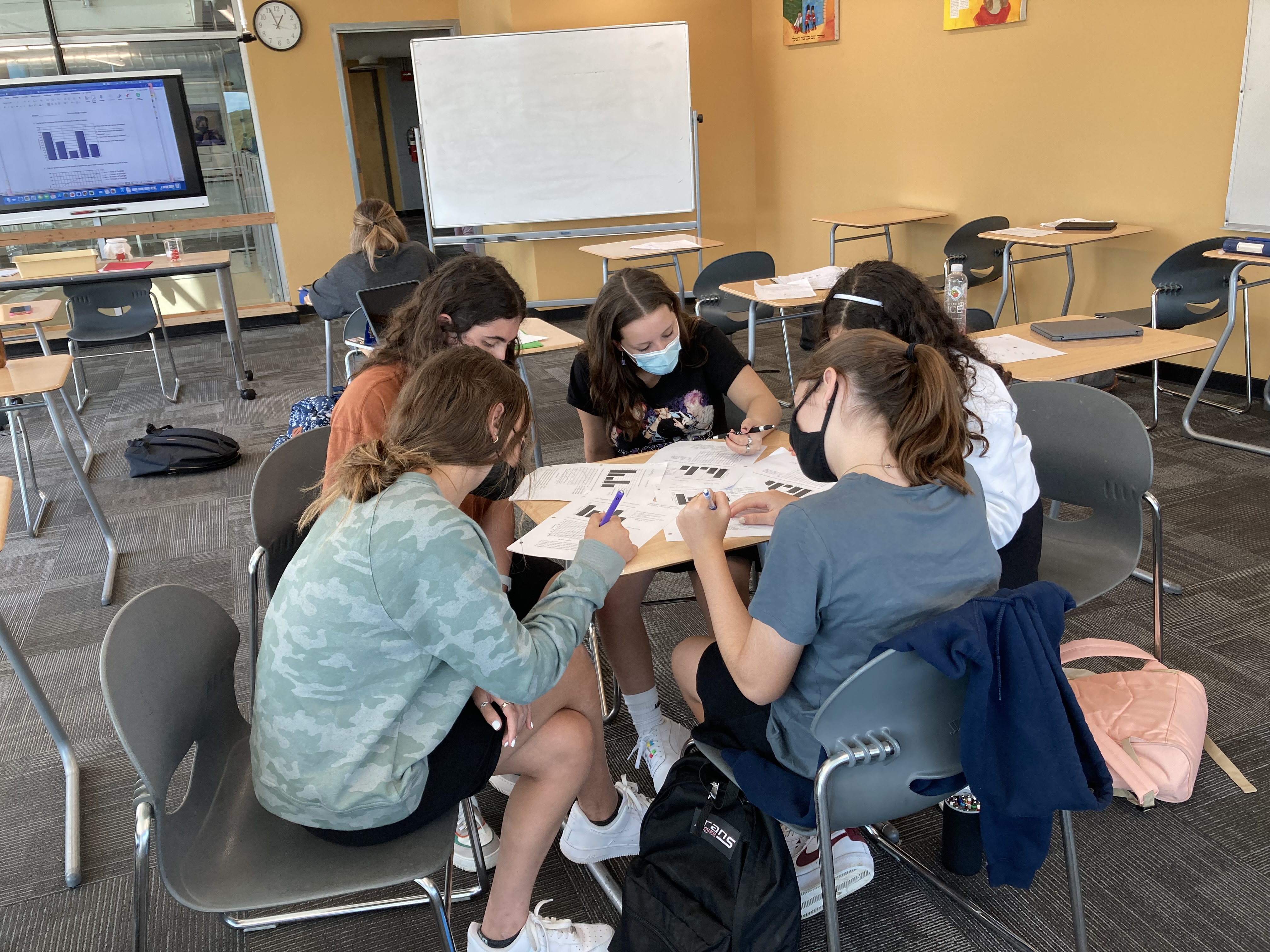

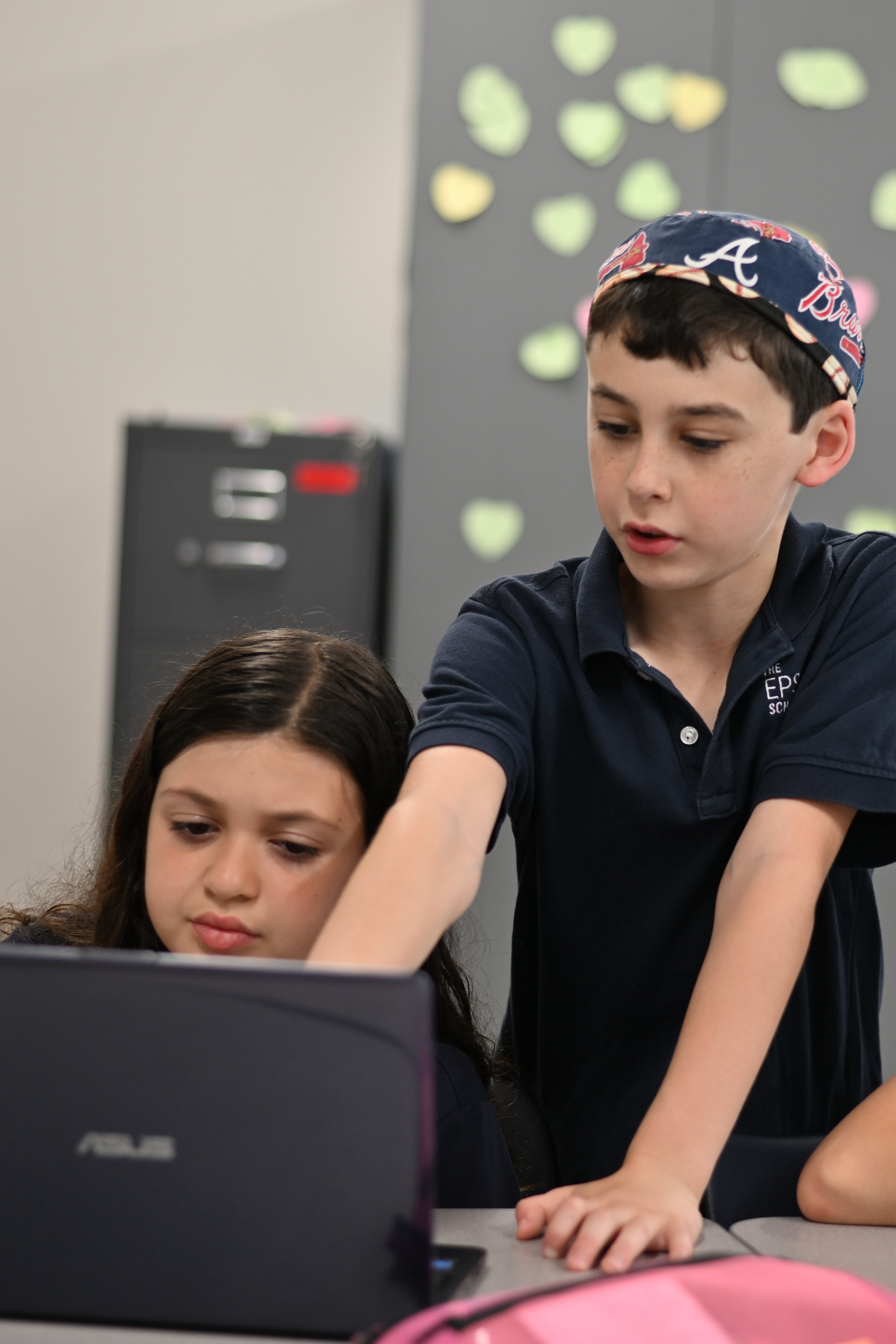

Instead of allowing young men and women to make career decisions based on their personal experience in school or theoretical conversations about teaching, we need to facilitate opportunities for them to teach, observe and experience the energy of schools. Over the past two years, the Chinuch Incubator has done this through the MafTeach program. The program sends college and graduate students to school communities around North America for a series of weekends (with some variations on length) throughout the year. The core component of all programs includes significant time in schools—observing classes, teaching regular or informal classes and meeting with teachers and school leaders. For programs that extended over Shabbat, fellows either join students on a shabbaton or are hosted in the local community where they run programs or continue interacting with students, teachers or other members of the broader school community.

Fellows walk away from their experiences with a greater appreciation for the profound impact teachers make. They learn of the incredible professionalism, thought and care teachers invest in their lessons and relationships with students. They experience ways in which schools and communities influence each other, and the important challenges and joys that come with working in a field where the boundaries between professional and personal life are often blurred.

Fellows also deepen their own sense of self-awareness, exploring through experience the unique strengths and weaknesses they might bring to a career in teaching. By interacting with teachers of varying personalities and styles, students of different ages, and in different types of schools and communities then they may have grown up in, fellows broadened their sense of how, with whom and where they might succeed.

Support

One of the most gratifying parts of my work with the Chinuch Incubator over the past two years has been my personal or small group conversations with students. Providing those even remotely considering a career in Jewish education with an address to turn to for questions and guidance helps translate theoretical possibilities in their head to something they can take action on.

Countless conversations have begun with, “I think I may want to be a teacher. What do I do now?” By connecting mentorship with a broader view of the pipeline years, I have been able to put a student in touch with particular teachers, recommend MafTeach and other experiences, or simply reflect back what I was hearing from them and give them some questions to consider. We simply can’t afford to lose potential teachers with passion, talent and interest because they are receiving clearer guidance in how to pursue internships in finance, computers or medicine and don’t know what comes next in education.

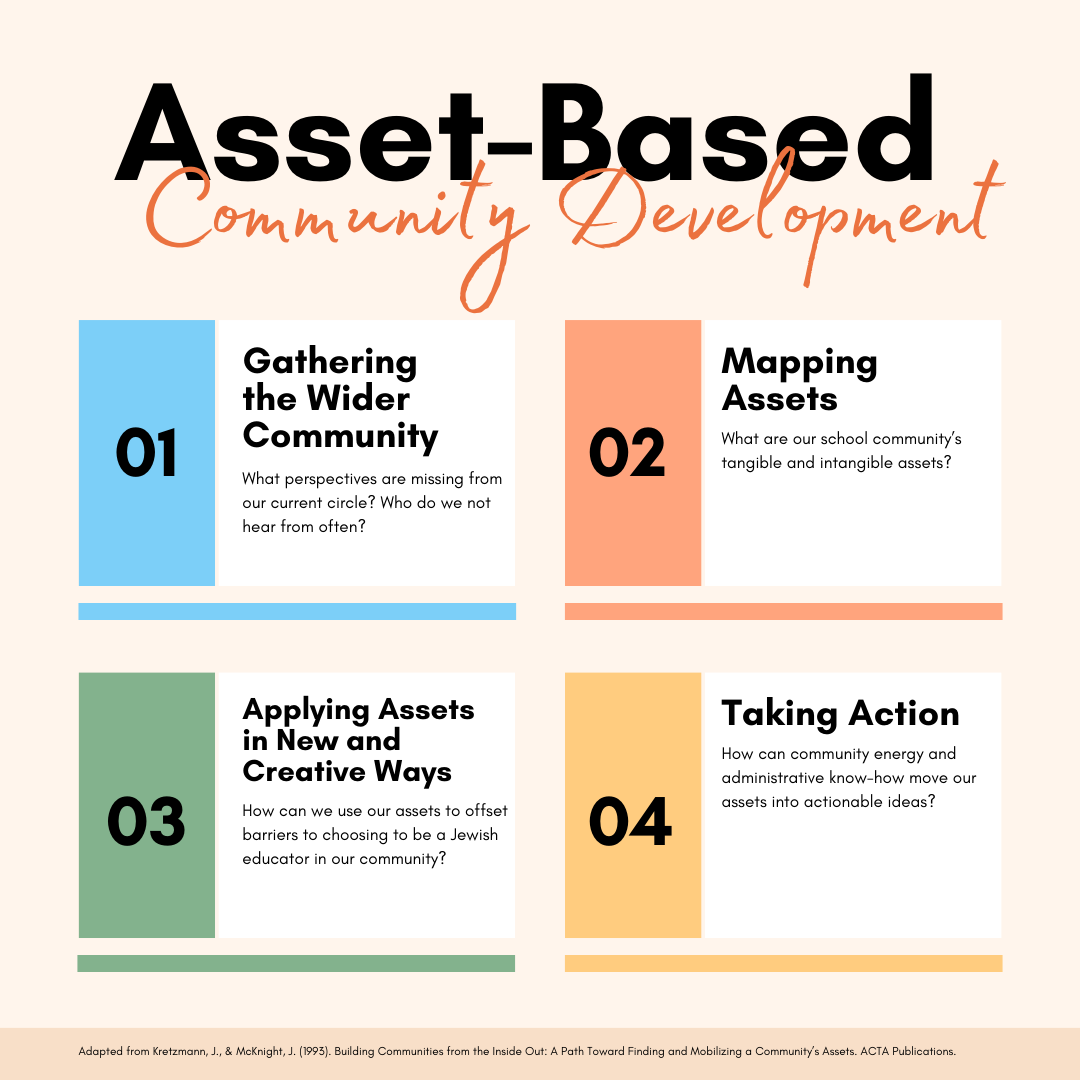

Clearing the Path

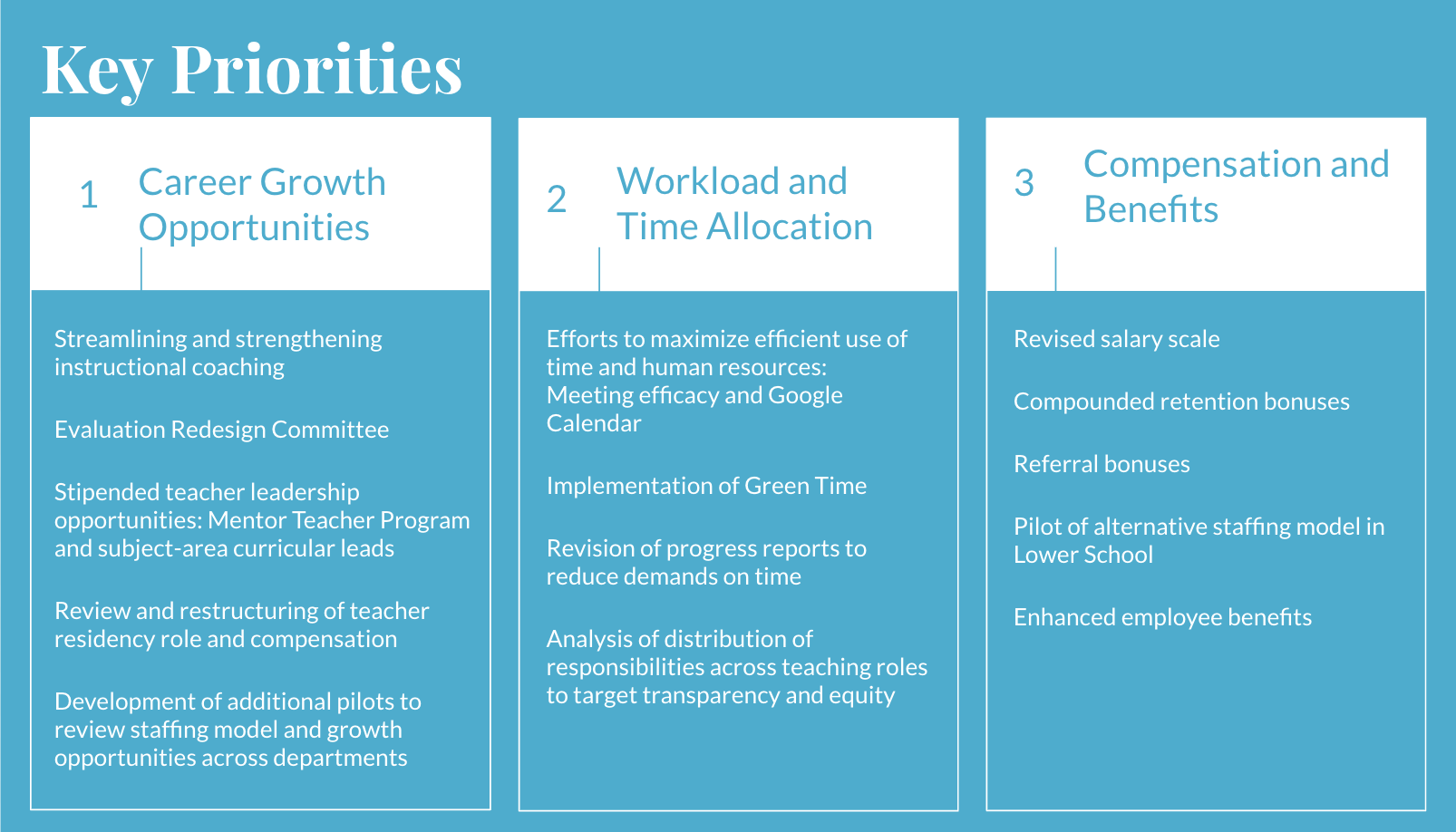

Till this point, as mentioned earlier, the Chinuch Incubator has focused on helping students develop their understanding of themselves and the field, increasing the “stimuli” that may draw capable students down the path of exploring Jewish education as a career. Tackling day school affordability, teacher salaries and communal perception may feel too large to tackle. At the same time, our work with those considering teaching has uncovered smaller scale inhibitors that get in the way of the inspired, passionate high school senior making it through undergraduate, graduate and/or semichah studies with sustained excitement that has translated to commitment.

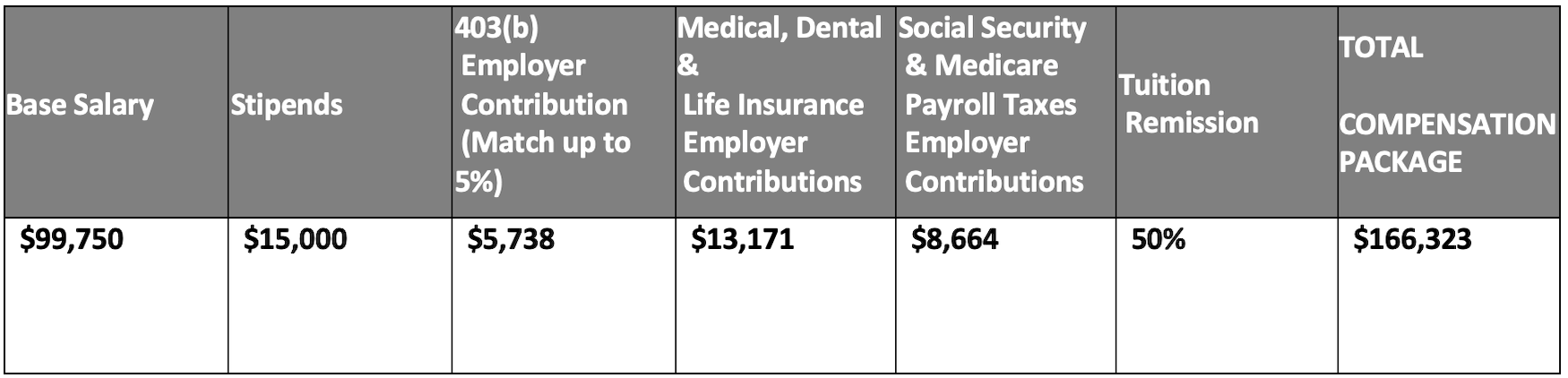

When students (and their parents, potential spouses or potential in-laws) know that the field they are considering will present financial challenges, the costs related to professional preparation feel even more daunting. Investing in those most likely to enter the field through finding undergraduate and graduate scholarship or providing living stipends can go a long way to helping talented students feel that if they are willing to make a sacrifice for the community, the community is willing to invest in making it as easy as possible for them to become the best teachers they can be.

We have found that, at least in the YU-affiliated Modern Orthodox community, a significant number of graduates of yeshiva high schools and yeshivot and seminaries in Israel enter their undergraduate years considering careers in Jewish education. We do not need to create interest “yeish m’ayin,” where it does not exist. Instead, we need to nurture and support those who demonstrate curiosity and talent.

Investing in increasing these students’ connection to, appreciation of and skills in teaching—together with clearing barriers during decision making years—can double or even triple the number of candidates entering the field over the coming years. We should be proud of the idealism, values and sense of mission that our communities are instilling in the next generation and do all that we can to ensure that those willing to translate that passion into a career can succeed in doing the same for the next generation.