Successful elements of PD that Hill and Papay highlight are collaboration time for teachers, particularly around instructional improvement; 1:1 coaching; and follow-up meetings so teachers can ask for and receive feedback to improve implementation of new strategies and tools. Hill and Papay also relay that PD in subject-specific instructional practices is better than building content knowledge alone, and that another key to successful implementation of new practices is “concrete instructional materials like curricula or formative assessment items.” Effective PD also has to include explicit ways to help teachers navigate and strengthen their relationships with their students.

Coaching Judaics Teachers

These findings are borne out by our coaching experiences in Jewish day schools. One familiar problem in Tanakh classes is that teachers want to improve students’ textual reading skills, but students’ level of Hebrew proficiency and desire to tackle text and commentaries in Hebrew vary widely. At the same time, Tanakh teachers want students to find Jewish texts meaningful and resonant. How to do it all?

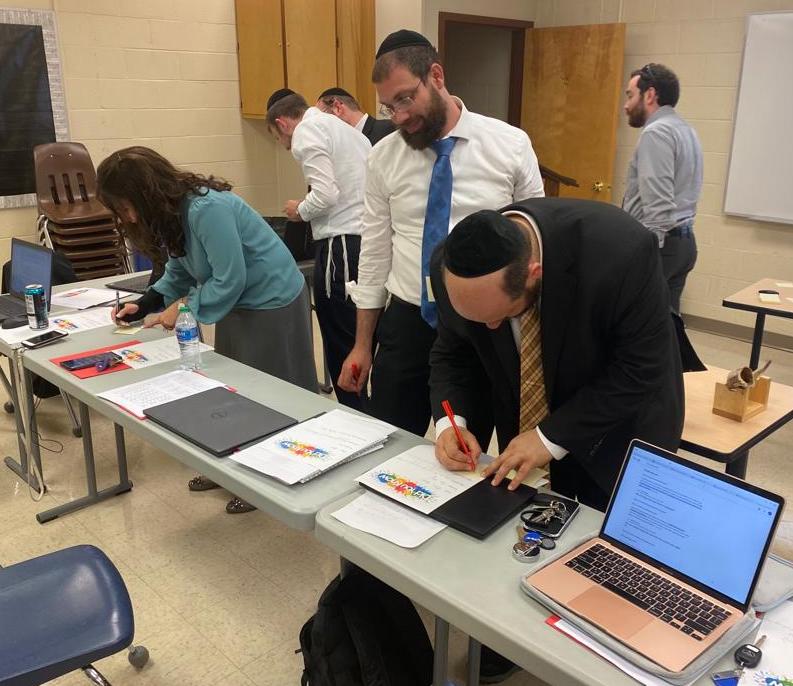

A BetterLesson Judaic studies coach, Leah Herzog, works with a Tanakh teacher who has been using differentiation to improve textual reading skills and engage students. Leah and the teacher experimented with different ways of allowing students to understand commentaries, either by using English translations or with peer coaching. In both cases, the teacher saw greater engagement; when students were able to use an English source and when they were able to help each other engage with a Hebrew one, they became more animated in their learning. Though Leah and the teacher’s focus had been differentiation, their discussions on diverse learners widened to include what the teacher’s overall content and skills goals are, and how the teacher wants students to develop values based on their Tanakh learning.

This anecdote illustrates why coaching is such an impactful professional development tool. It allows teachers to apply pedagogies developed in general education in ways uniquely suited to a Judaic studies classroom, and provides the time and space in which to experiment with the strategies, fine-tuning them for a particular classroom and group of students. Coaching with a mentor in a teacher’s school—either a peer or administrator—also creates close bonds and positive working relationships. Sharon Freundel, managing director of the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge, emphasizes, “Educators realize the importance of paying individual attention to each student in order to elevate their learning and develop a relationship with them. Teachers, too, benefit from the same kind of attention; they elevate their practice, and the student is the ultimate beneficiary."

In one school that Tavi and Tikvah work with, a middle school Judaic studies teacher has been using creative assessments in her class and wanted to try Socratic seminars. Many examples of them can be found online, all in general studies classes. With the teacher, we adapted the Socratic seminar guidelines for her Navi (Prophets) class, and after watching videos of history teachers using Socratic seminars, figured out how the teacher wanted to run hers.

The teacher reported that the students loved the seminar, asking to do it again, and said it taught them to actively listen to each other. Another outcome, one that touched her the most, was that a student who struggled socially shared an anecdote that captured the attention of her classmates, who peppered her with questions. The teacher had never before seen this student as engaged socially, and we remarked that it was powerful to see this in a Judaic studies class, where we especially want students to feel a positive connection to each other and their learning.