Calling, Growth and Satisfaction

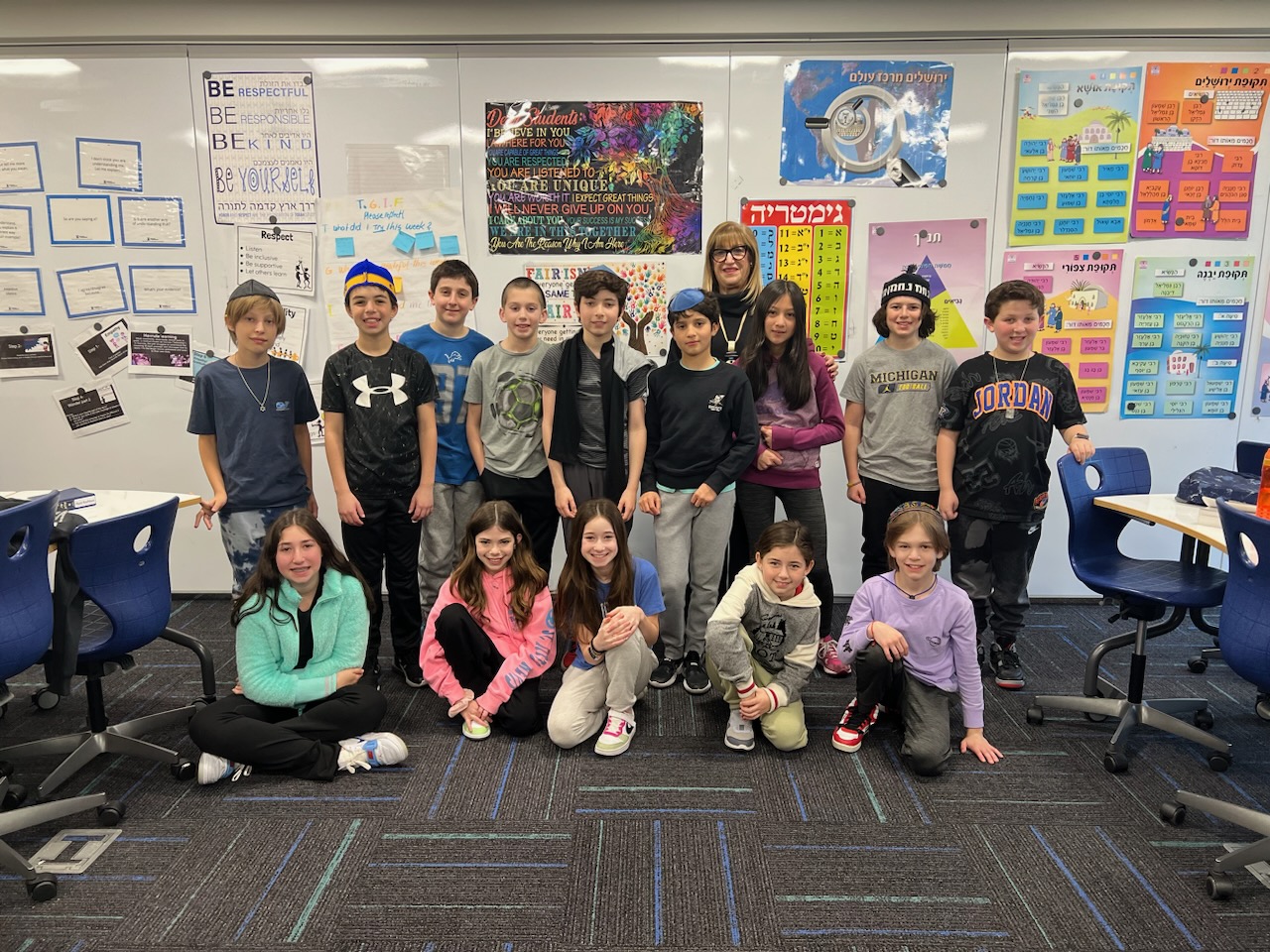

Clara Gaba, Judaic Studies Teacher, Hillel Day School, Farmington Hills, Michigan

In today’s world, filled with headlines about teacher shortages and demanding careers, many might wonder why someone would choose to stay in the classroom for decades. The answer, for me, is simple: It’s the most rewarding profession imaginable.

I was born and raised in Israel. I studied Bible and archeology, but never intended to be a teacher. Moving to the United States, I dreamed of a career in accounting until someone asked me if I was willing to be a guest teacher for them in an afternoon school. I was never in a classroom before, neither did I have the credential to be a teacher. The initial experience as a guest teacher ignited a realization that this was my calling, motivating me to pursue the necessary education and certification.

Over the years, the joy of touching young souls, witnessing their growth, and contributing to their education became a lifelong mission that continues to energize me. The impact on students’ lives and the deep connection to my calling have been enduring reasons for my commitment to teaching. I started as an afternoon school teacher 38 years ago; six years later, I became a day school teacher and remain one today, energized to go as many years as God will allow me.