Traditional text learning tends to occur sitting around a table, studying in pairs, or as a group. What happens if we get up from the table and study using our bodies? And what if we do that study using circus?

Yes, I know, what does circus have to do with Jewish life, let alone with studying Bible! We have learned, however, that there are many connections between circus and Judaism (and many Jews involved in circus history!). And we have learned to approach the biblical text using human pyramids, tight-wire, juggling and trapeze to embody the text and learn to think with our bodies together with our minds.

Embodied Learning

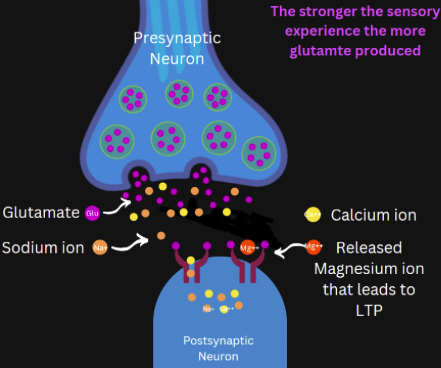

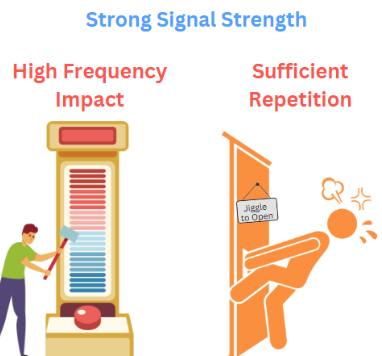

Embodied learning is the belief and knowledge that our bodies are capable of making sense of all manner of information, and that relying only on the power of the brain to process information effectively reduces our ability to understand the world by an incalculable factor. How much more could we all learn, process, metabolize and express if we understood the intelligence inherent in our physical beings and the intellectual power our bodies could generate.

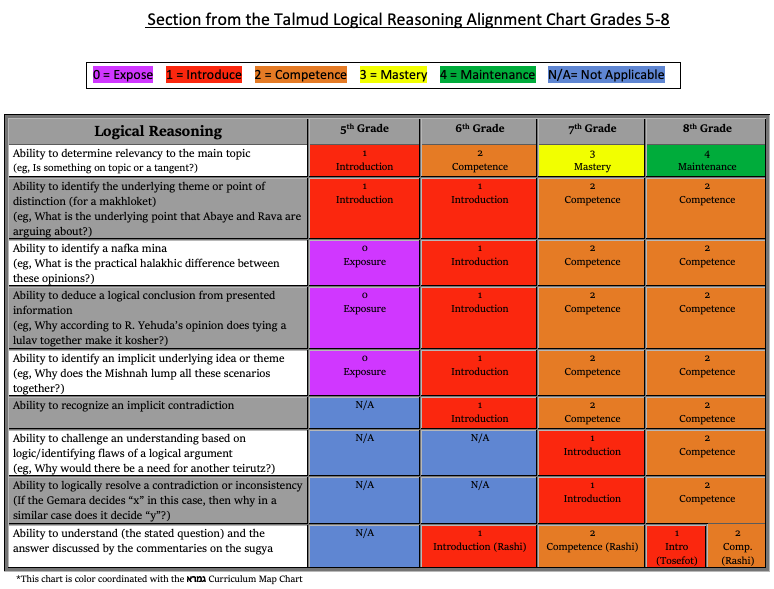

At the Academy for Jewish Religion, a pluralistic rabbinical, cantorial and graduate school, we have spent real time bringing arts into our curriculum, enabling students to use a variety of artistic media to study sacred text. “Sacred Arts” joins and elevates the two foci of our work, sacred text and artistic exploration, so that together they add new sensory experience to the already vast corpus of interpretation Jewish tradition embodies. Our understanding of Sacred Arts is a method in which art forms are used as vehicles to process text. It treats both the text and the art as serious academic disciplines.

To be clear, this is not art as arts-and-crafts or playtime (although employing art methodologies can be quite fun). And it is not using the text as a jumping-off point to produce art. Rather, it uses the artistic process as a way to understand the text, as a way to study the text. It entails the use of art methodologies as a rigorous discipline.

The Arts as a Means of Processing

Jewish text communicates on a variety of levels to a variety of students possessing a variety of intelligences. Our method affirms to artists that their ways of understanding are essential, valued, intrinsic and not tangential to their experience of Jewish texts and Jewish life. (This is particularly important in Jewish day schools, where artistic children sometimes feel disenfranchised.) The arts can serve as a means of processing—as important as any other approach to study.

One might think that this work is particularly aimed at kinesthetic learners, or at those for whom art is a primary method of communication. It’s important to recognize, however, that studying through circus works for everyone. Even those of us who love traditional text study, sitting around a table together, benefit in so many ways from studying through circus.

Chiddushim from Circus Exercises

This mode of study is best understood through examples. As a personal example, I have been studying and teaching the Bible for many decades, and for much of that time I paid very close attention to feminist readings of the Bible. I have spent real time on the wife/sister story in which Abraham passes Sarah, his wife, off as his sister in order to protect himself (Genesis chapters 12 and 20). I had always read this as Abraham being abusive to his wife, Sarah, by putting her in danger and creating a situation where she was taken into Pharaoh’s house to be either potentially or actually subject to sexual violence.

During a Sacred Arts circus class, I climbed onto a rolla bolla, a board on top of a cylinder where one stands and strives for balance. While standing on the rolla bolla, I then read the wife/sister story again. Because I was feeling unbalanced on the apparatus, and concerned about falling, I was suddenly filled with a new empathy for Abraham. I felt his struggle, his fear, and his pain. This is not to say that Abraham was right in his actions, but this new empathy led to a richness in my reading that had not been there before. A very few minutes on the rolla bolla allowed me a new reading of the text.

Another example occurred at a Jewish education conference where we happened to have a number of parent-child pairings in the group. We were studying the Garden of Eden story (Genesis 3). One of the groups created a pyramid in which a child was leaning on a parent, and then, as part of the plan, the parent needed to step away to move to a different part of the pyramid. This was meant to be representative of God’s role in the story, first being leaned upon, and then moving into a different position in relationship to the humans.

In our structure, the child was really only leaning on the parent in theory; there was no significant weight on the parent, and yet, when discussing it later, the parent had a difficult time changing positions. She felt uncomfortable moving out of the position of being leaned upon, even though she knew her child would not fall. She sympathized with God’s potential “parental” anxiety in the Divine relationship with Adam and Eve as they emotionally age through the chapters, and where God needed to adjust to a new relationship with the humans.

Given that there was such a presence of parent-child pairs in the group, this led to a powerful conversation about the roles of parents and children, how to let go, when to let go, etc. We also discussed deeply the relationship of God and the first humans using parent-child imagery. That is a standard reading of the narrative, yet it was one that we had not shared in that group. We came to it purely through embodying the text, not through teaching. It was a very powerful moment for all attending.

Imagine for a minute how your students would react if they felt they were studying Torah while walking a tightwire? If they gained new insight on the book of Ruth while hanging from a trapeze? Yes, it really is as exciting, fun and valuable as it sounds. Our new book, Under One Tent: Circus, Judaism and Bible (edited by Michael Kasper, Ayal Prouser, and me) explores this topic including articles by an international group of educators, scholars, and circus professionals. It explores underlying theory, examples of the use of movement in educational settings ranging from preschool through adult learning, and connections between circus and Jewish life.

Similar work can be done with a variety of art forms including visual arts, writing, storytelling, movement and dance, and music. In our Sacred Arts work using those art forms, we took a similar approach, using the art to process the text, not aiming to create beautiful art or even finished products. This work once again confirms the adage that there is no limit to ways to approach the Bible.