Given the current and quickly changing digital landscape, every school should review its responsible use policy to ensure that the language is still applicable. As our school reflected on the updates we needed to apply to ours, we began to see the document less as a policy and more as something like a prayer, though it took us a while to come to this understanding.

In November of last year, our school kicked off a digital wellbeing initiative with the mission of optimizing our technology policies and platforms, aligning our official and unofficial digital wellbeing curriculum across divisions, and delivering adult education on digital wellbeing to faculty and families. The initiative’s steering committee is composed of classroom teachers, technology integrators, social-emotional leadership and administrators from all grade levels, as well as parents and members of our communications team.

Our first deliverable, by popular demand, was a set of workshops on how to implement a family media agreement, based on the framework offered by Common Sense Education. As we prepared for the workshops, we found that we needed to make clear distinctions between “guidance for families” and “school policy,” and so we initiated a parallel effort to update our student-facing responsible use policy.

Listening to Students

Meanwhile, our entire steering committee read Behind Their Screens: What Kids are Facing and Adults are Missing, by Carrie James and Emily Weinstein, and our eyes opened to so much about the experiences of teens as they navigate lives mediated by digital platforms. James and Weinstein surveyed over 3,500 teens about their experiences and relationships with social media and other digital technologies, and when sifting through the results, they found that the teens’ experience was so vastly different from their own that they needed help interpreting the data. They created a Youth Advisory Council, composed of a diverse collection of teens who informed their analysis generally, and specifically influenced the insightful “What Teens Wish Adults Knew” sections at the end of each chapter of their book. After our committee discussed Behind their Screens, we knew we had to add student voices to our policy development work.

Our high school student government’s student experience subcommittee met to read and respond to the first draft of our new responsible use agreement, note any language that is unclear or points that might be missing. The agreement was full of “I will…” and “I won’t…” statements, and organized around Common Sense Education’s digital citizenship curriculum topics, such as privacy and security, digital footprints and identity, and relationships and communication.

The students read the agreement and asked a few questions, including whether the way some of the statements were worded implied that they applied to the use of their personal social media accounts when not on school property. This sparked a robust discussion about all behavior, online and off, reflecting on them as a member of the community.

And then they opened up a bit. One pair of students, and then another, and another, began to admit, tentatively at first but then more openly: They, or their friends, engaged in almost all of the practices that the agreement stated they would not do. “Who hasn’t said something, jokingly, in a post, that might be construed as a little bit mean?” “We all forward pictures and screenshots without asking permission.” “I know people share passwords…” “It doesn’t feel like true misconduct, or actually harmful...but…”

When I looked at the list again through this lens, I saw what they saw. “Okay,” I said, the proverbial drawing board looming in my mind’s eye, “One more exercise.”

I asked them to go back through the “I will…” and “I will not…” statements and circle each one that they—or their friends—“sometimes” or “lightly” violated. “Be honest,” I said. “No judgment here. I came here to learn from you.”

No pair circled every point, but among the four pairs, every single point was circled. It was clear that we had a complete set.

I brought the problem back to my team, demoralized. “What if you focus on the why?” someone asked. “Instead of ‘will/won’t,’ focus on the consequences. The harms to themselves and others.”

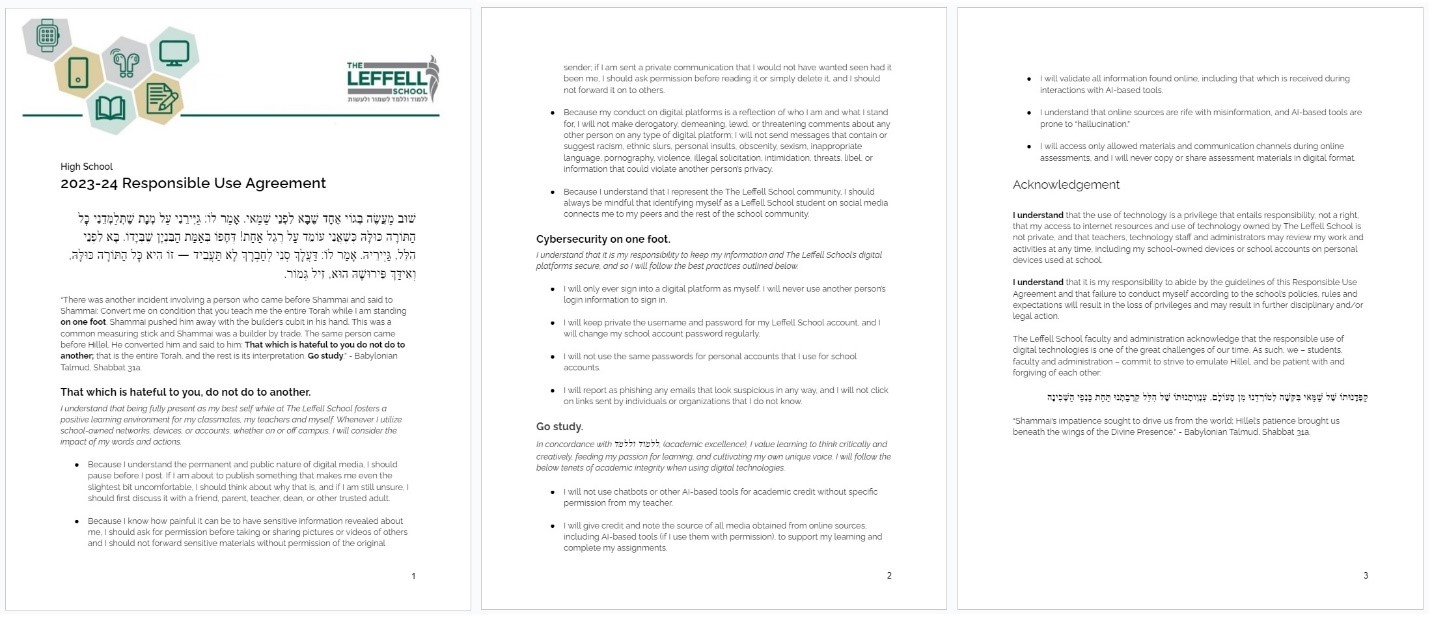

Patient and Forgiving Use

So a new version of the agreement began to take shape, with statements such as, “Because I know how painful it can be to have sensitive information revealed about me…” and “Because my conduct on digital platforms is a reflection of who I am and what I stand for…” Although the section that specifies cybersecurity safety practices retained its “I will…” and “I will not…” structure, the digital citizenship statements now begin, “I should…” and “I should not…,” a nod to the difficulty of always being our best selves online.

The new version of the agreement is also informed by a key lesson of the “why” of it all that we learned from Behind Their Screens. They show how our children are growing up in a world where the most private, precious work of identity formation—defining who they are and who they want to be—is being done on a stage that is very public, very permanent and very unforgiving. It is hard for the adult members of our digital wellbeing initiative’s steering committee to relate, because our adolescent stupidities and unkindnesses were not documented for the permanent record in quite the way our students’ are now: public by default, infinitely replicable, searchable, algorithmically reinforced and with an absence of the physical cues that attend real-life communication.

James and Weinstein show how these affordances of digital platforms deeply influence and constrain how teens develop their sense of self. With teen mental health in steep decline, the stakes have never been higher for teens to find a way toward not just responsible but socially and emotionally healthy use of the technologies that pervade their lives. The authors helped us to see that, perhaps even more than the responsibility to pause before they post—to remember to keep sensitive information private, to seek consent when required—we need to encourage teens to be patient and forgiving of themselves and of each other. And we have to somehow teach ourselves this lesson, too.