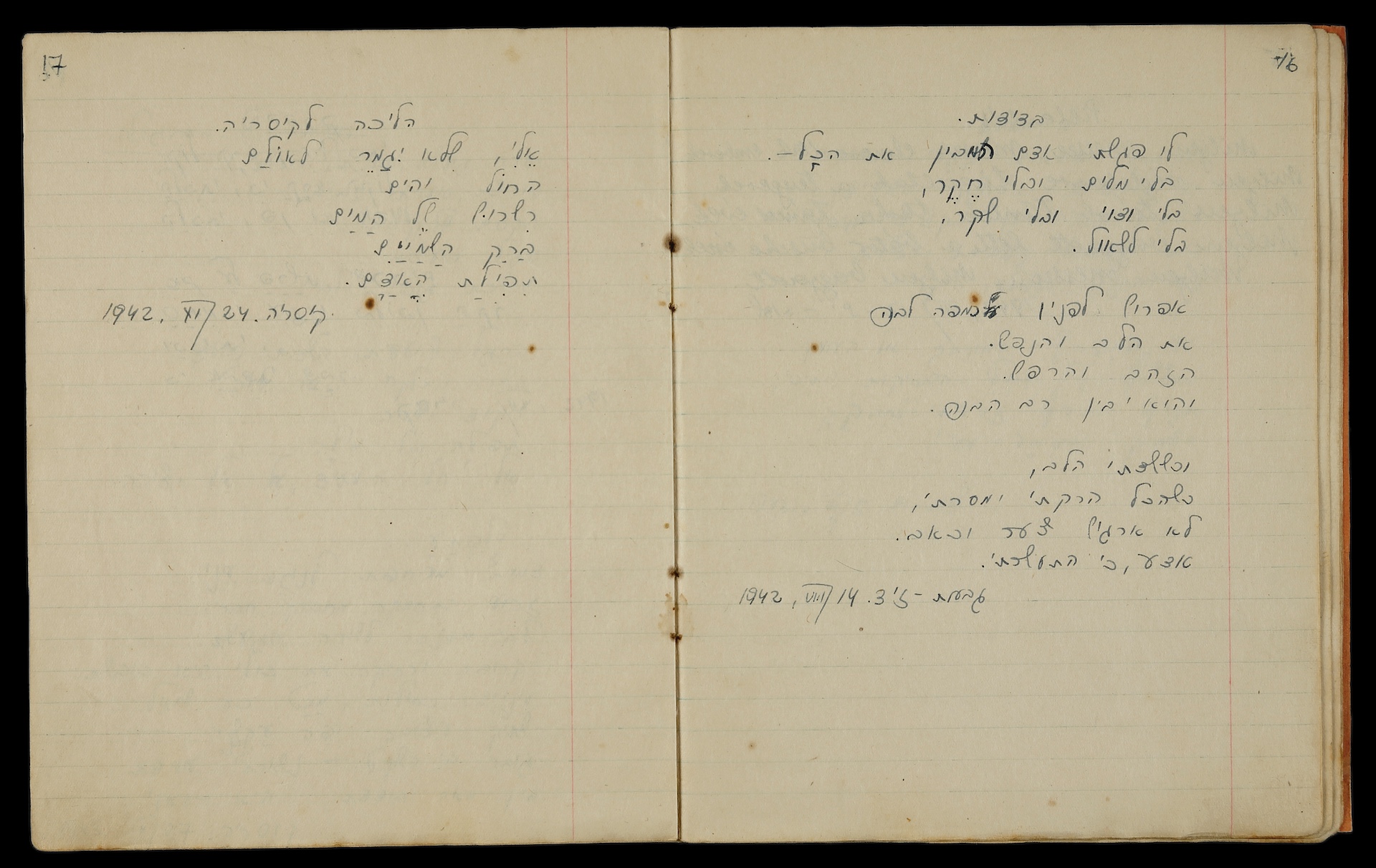

Hannah Szenes' diary pages 54-55, Palestine, November 1942-February 1943, The National Library of Israel. Photography by Ardon Bar-Hama.

Among Szenes’ personal belongings housed at the NLI is her original, handwritten poem “Halichah L’Caesaria,” colloquially known as “Eli, Eli.” This is a poem whose words are easily searchable online, but it is not the same as reading them out of her own notebook and seeing them in her own handwriting. With the opportunity to view the original copy of this poem, students can easily identify a spelling mistake common among emerging Hebrew students: Szenes spells “olam” with an aleph rather than an ayin.

Without this personal artifact, Szenes is a name among many other historic figures students encounter; someone who lived before their time, and even before their parents’ time, who was from a foreign country and spoke a foreign language. She was someone whose identity does not automatically resonate with American students. However, when given access to her personal items—her handwriting, report cards, her spelling mistakes—Szenes comes alive as a person who wrote this poem at an age not much older than our high school seniors. She becomes someone relatable and is brought to life as a young person who was learning Hebrew just like they are. With partnerships like those the NLI is working on with Wikipedia, Szenes’s personal archive will not only be accessible through the NLI’s online catalog as it is now, but it also will pop up within her Wikipedia page—often the top result in a student’s Google search.

Now consider a historic figure who is not associated with Jewish history: Sir Isaac Newton. Perhaps a STEM teacher is looking to integrate Jewish content into the math and science curriculum. Where would this teacher look for resources? A Google search of “Newton and Jewish” won’t bring you directly to the NLI’s catalog, but it will pull up a Google Arts and Culture exhibit featuring Newton’s theological papers—among them, a manuscript with Baruch Shem Kavod Malchuto L'Olam Va’ed, written in Newton’s own hand in Hebrew characters. With this image, a teacher can illustrate that this historic figure, best known for his mathematical principles, not only read and wrote in Hebrew, but scribed the same words our students are taught to recite each day.

NLI’s partnership with Google Arts and Culture already has made this resource readily accessible, a resource that not only expands students’ understanding of Isaac Newton, but also invites them to draw unique points of connection between calculus and tefillah. As AI technology continues to evolve, these points of connection will only become more frequent. Looking ahead, I anticipate that AI technology will “read” a handwritten manuscript like Newton’s theological papers, identify its liturgical references and suggest it as a resource for a student researching the Shema.

A World of Possibility

While AI raises challenges, and schools do need to think intentionally about how to approach them, AI is opening windows into the past and ultimately enabling the sparks of meaning and connections that teachers work so hard to foster in the classroom. With modern technology, the NLI is able to give access to so many treasures that 20 years ago were only accessible to a very small, scholarly group of learners within the confines of the library building. When considering AI technology, we must remember that “our job is not to compete with it, it is to complete it,” as the NLI’s head of the digital department reminded me. As educators, our job is not to work against AI, it is to work with it, helping our students use it responsibly and taking advantage of the world of possibility it presents.