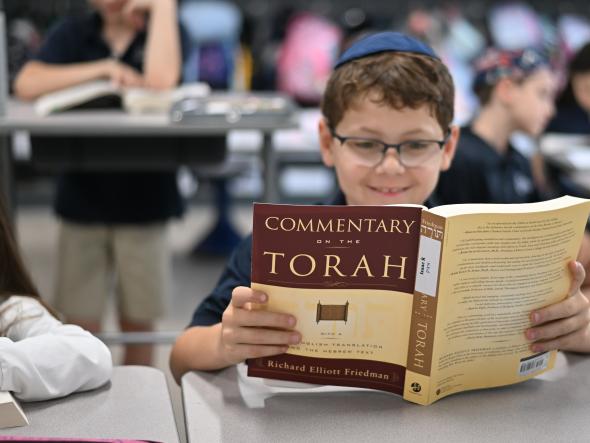

But AI is moving fast, and these problems are solvable. Decades of building Torah databases have yielded exactly the data set needed to design an AI that could, indeed, be a tutor, classroom aid and textual guide all wrapped up in one. More than being convenient, these tools might imbue learners with the confidence to ask hard, direct questions.

All of these developments are stops on the way to a grander prize: the development of a conversational AI that embodies the entirety of Torah. Such a model, presented as a “person,” would have the ability to speak on behalf of the Jewish tradition as a whole, or whatever part of it happened to be of greatest interest. Imagine an AI embodiment of Deuteronomy, or Rabbi Meir, or Glikl of Hameln—and imagine having them speak to one another. AI as Torah personified would quickly make its way into the classroom and could be a valuable third partner in any havruta. Such an AI might spur a great deal of textual exploration and high-level understanding of different parts of the tradition. Add in analysis and use of sound and images, and the possibilities are almost limitless.

I have confidence that these AIs will be built; Jews have long been at the forefront of digitized religious learning, and I expect this to continue. The AIs I am describing have the ability to open up Torah lishmah to people who might otherwise never have been interested, and they will create new possibilities for those already invested.

Three Guiding Principles

That said, the devil is in the details. It is important to implement these AIs in a way that emphasizes that Torah study is not like other forms of study, does not leave users overly reliant on the AI as the font of all Torah knowledge, and inspires the creation of new ideas. To that end, here are some specific suggestions for how an AI programmed to enhance Torah lishmah might be productively designed.

Better to say too little than too much. The current cutting-edge AIs all suffer from “hallucinations,” which means they make up false information. Given that Torah study involves thinking carefully about each and every word and phrase, the stakes for making up new Torah are unusually high; in addition, the things not said are often as interesting as the things said. To that end, Torah AIs must be scrupulous not to fabricate information and to make the user aware of the limits of their knowledge. This also gives space for users to develop their own ideas without falsely believing that someone else has already had that same thought.