The Show Must Go On(line): Virtual Fiddler

When our campuses closed due to Covid-19, the cast of Fiddler on the Roof was only weeks into rehearsals. Most schools had canceled their spring performances, but our cast was determined. The students and show leaders met over Zoom to discuss whether they should continue. From the outset, there was a resounding response from the students that “The show must go on.” As one sixth grader noted: “The coronavirus has already taken so much from us—we can’t let it take our production away, too.” And so began our journey into a reimagined, virtual production of Fiddler on the Roof.

Applying the design thinking approach, our directors asked the students to reimagine the musical, to consider what to keep from the traditional musical model and how to adapt it to changing circumstances. They had to rethink many aspects of the show that are not possible to replicate with social distancing restrictions in place. They recreated scenes featuring multiple characters in dialogue or song together, and the newly interpreted scenes managed to be both resonant and modern. For example, the “Matchmaker” number has our young women sharing the same hopes, dreams and fears in song, but their “matchmaker” is an online dating app.

Similarly, whereas in the original show “To Life” celebrated the simchah of a planned wedding, our middle school production presented this song as a tribute to the students whose bnei mitzvah were revised or postponed. The changed medium also provided new opportunities for creativity that would not have been possible on stage, as in the scenes when Hodel is filmed singing “Far From the Home I Love” in front of a historic B&O railroad station, and when our Fiddler character plays her violin on the roof of her family home.

The experience held moments of unexpected joy, too. We learned with renowned producer and composer Zalmen Mlotek (of the hit Off-Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish). He even recorded a number for inclusion in our school musical! Extensive outreach to press got our story picked up by JTA, and readers across the country saw our middle school production. In addition, our show was streamed on the website of Washington Jewish Week, which also ran an article about our production.

Virtual Fiddler was the embodiment of our school’s culture of creativity, innovation, courage amidst uncertainty, and faith in the capability of students, alongside our tradition of parent engagement. In addition to a teacher/producer, two parents served as co-directors and they were supported by a troupe of volunteers with film and theater backgrounds and expertise in Yiddish, Jewish history and Jewish literature. We were inspired by the creativity, courage, talent and resilience of our middle school actors and the commitment of the volunteers who supported the student thespians to bring this production to life. Like Tevye, we were balancing tradition with changes that sometimes come unexpectedly.

Virtual Learning: An Opportunity for Student Collaboration

Students learn best when they’re learning with each other rather than from teacher- delivered content, especially when learning online. In our fifth-grade classes, we accomplish this through real-time collaboration, by creating opportunities for an authentic audience, and by keeping students’ social-emotional wellness at the heart of our teaching.

REAL-TIME COLLABORATION

During our daily live Zoom sessions, we strive for students to collaborate in breakout rooms for the majority of the meeting. Working with their peers, students solve challenging math problems, collaboratively analyze poetry, co-create original writing, provide feedback to one another, and even work in teams on virtual escape rooms. We utilize Google docs so that students can work together on assignments in real-time despite being distanced from each other. Prioritizing real-time collaboration during virtual learning ensures that our students stay engaged with the curriculum and continue to develop the social skills needed for academic success.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR AN AUTHENTIC AUDIENCE

Our students regularly complete work independently as part of a larger project, which is then shared with a wider community audience. Last spring, they used Padlet to create an interactive Revolutionary War Museum, allowing them to teach their peers about different events and historical figures of the Revolution. Each student curated their own exhibit and then all students had an opportunity to “visit” the museum virtually.

This was one of the many opportunities where parents, teachers, and members of the community were welcomed into our “classroom” to learn from our students. We frequently showcase student writing through community events when we are physically together on campus, and we have found making these events virtual has made them accessible to a wider audience. Virtual learning has broken down the walls of the classroom and extended the opportunity for students to receive feedback from members of the school community at large.

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL WELLNESS

Knowing that our students are missing the social interaction that is inherent on campus, we regularly create non-academic spaces that foster peer-to-peer interaction. Last spring, we created a digital yearbook so that students had the opportunity to sign one another’s autograph pages, send well wishes and share memories from the school year. We make sure to celebrate all student milestones, and our fifth-grade leaders even collaborate to create personalized birthday videos for every student in our school who celebrates their birthday while we’re distanced. These rites of passage, which are important to students when we are on campus, become even more essential to re-create when students are distanced from one another.

Virtual learning has empowered us to look closely at our school values and ensure that they are prioritized even as we redesign our curriculum for this learning environment. With student collaboration at the heart of our decisions, we have been able to create learning experiences that are highly engaging and memorable for our students.

Blogs and Stories

Collaboration and distance used to seem like a paradox. Now, they are a daily part of teaching during Covid. How can we teach students the important skills of collaboration, while oftentimes there is a lot of space and distractions between us?

At our school, one way we do this is with blogs. In classes from third to eighth grades, students utilize blogs to collaborate in a variety of ways: within the school, with their parents, and on a community and global scale. For example, in one class students connected with people from all over the world and collaborated with peers in a classroom in Malaysia, commenting on each other’s social studies blogs while forming friendships.

Blogs are frequently used as documentation of learning. Students blog when working through the design thinking process, participating in Genius Hour or reflecting on final drafts of their writing. Blogs are also used as documentation for learning, such as to record research, to document book club meetings or to solve math challenges. Teachers use blogs to showcase student work or communicate about what is going on in their classes. Overall, our blogs help us stay connected, even from far away.

As a Jewish school, maintaining a connection with Israel is also important. Each year our eighth graders build a connection with our partner school in the Kinneret region, Kadoorie Agricultural High School. When they visit Israel in May, they have already developed a relationship with the kids from the school, and they do homestays with their Kadoorie friends. Many teachers from around Milwaukee are partnered with teachers in the Kinneret region through a program called P2G (Partnership 2gether), to keep Milwaukee Jewish students collaborating with Israeli students, even during a pandemic.

An internal cross-grade level collaboration, started in 2006, has seventh-grade students write a fictional narrative for a second-grade student based on their interests. First, the seventh graders interview the second-grade students. This year this will be done through Zoom. This interview is a way for the seventh graders to find out all about the second grader in order to write their narrative with the second grader as the main character, surrounded by all the people, places and things they love.

Next, students work with me in English class and we move through the writing process. Often, students will continue to collaborate with their partners, in order to be sure to capture their interests perfectly. When ready to publish, the books are illustrated and then printed and bound. Finally, we visit our second- grade friends and read them their book. This year, students may record themselves reading the book.

S'mores a la Zoom

There is no doubt that student collaboration adds many dimensions to learning: discussion about a given topic, deeper understanding of material, even adding a level of enjoyment to the most tedious of subjects. Transitioning to distance learning meant the transition into survival mode—as parents, students, educators, and as humanity. Student collaboration was the furthest thought while lesson planning—that is, until the shock wore off. It was then time to get creative in this new environment. My usual bag of classroom tricks wouldn’t work online, and this had me stumped. The turning point was realizing that it was not an unsolvable problem but a matter of reframing the situation, “Look at what we have and how can we use it” rather than “this won’t work because…”

During normal times, one of the fun hands-on activities that is popular in third grade is an “achdut bonfire,” in which after discussing the themes of achdut and ahavat Yisrael (Jewish unity and love), each child gets a precut piece of tissue paper and sticks it onto an overturned clear bowl. Before doing so, the student shares the resolution they will attempt in this area. After all the pieces are stuck, I turn on an electric candle under the bowl and we enjoy s’mores around our bonfire, sharing stories and continuing the discussion.

On Zoom, the s’mores part was easy to do, as was the discussion. The twist for the bonfire was doing one virtually and having the students “build the flames.” Enter ”virtual whiteboard” with open control setting and voila, the magic happened.

To revisit the theme of achdut during another lesson, we explored the importance of effective communication in another lesson. Again using the virtual whiteboard and open control, I asked the students to draw a picture as a group, but their microphones had to be muted and there was to be no communication. After a few minutes and multiple complaints of “Who erased my picture?” and “Who is drawing over my picture?” I asked for “hands off,” cleared the screen, and said, “Let’s try this again, but with communication this time.” The result was an organized picture in which each student had her place to draw. The added bonus was watching the natural leaders shine as they communicated and spoke with each other about the plan for organization.

The shift to distance learning presents many challenges, but collaboration should not be one of them. There are many tools that can be used online, for both synchronous learning and asynchronous learning, to enable students to collaborate. This is the time to be more creative in encouraging students to share their voice and take ownership of their learning. If only we could do the same with hugs and high-fives!

Research Corner: Measuring the Pulse of Jewish Day Schools

At Prizmah, we believe in the power of data-informed decision-making. Our Knowledge Center collects and houses data, research and resources for and about Jewish day schools and yeshivas. To support field leaders, we conduct original research, gather and share data, report on Jewish day school trends and partner with organizations to further important research in Jewish day school education.

Since the start of Covid-19, we conducted two pulse surveys meant to understand the state of the field of Jewish day schools and yeshivas at that moment in time. Our second survey, fielded in August, showed that most schools planned to have in-person classes. More than 80% of early childhood programs planned to open in person, close to 70% of grades K-5 and 65% of grades 6-12. 46% of responding schools planned to give their teachers the option to work remotely if needed. We found that schools widely deployed surveys and “town hall” meetings as mechanisms for feedback and communication during the last semester of school.

Covid-19 is creating a financial vortex for many schools. 80% of schools indicated an increase in tuition assistance for the 2020-2021 school year. The average increase in tuition assistance is $145,000. Moreover, schools that opened their buildings had additional expenditures such as PPE, cleaning supplies, building modifications, outdoor enhancements and additional personnel. These totalled $173,031 on average, with the highest reported total costing $909,000. Per student, the average increased cost from all Covid-related expenses is $669.

On enrollment, 42% of schools reported an expected decrease, while 37% anticipate an increase. Nearly 60% of schools are projecting a downturn in fundraising.

Most schools had budget cuts for the 2020-2021 school year, with the top cuts reported in professional development, non-program staff and administrative staff. On a positive note, 65% of schools reported an increase in enrollment inquiries, the majority coming from public school families. Both Orthodox and non- Orthodox schools reported an increase in enrollment inquiries. When looking at the enrollment sizes of schools reporting an increase in inquiries, 40% of these schools are schools with enrollment under 200 and 36% have an enrollment between 200 and 499.

While the future is unknown, this report demonstrates some of the ways that Covid-19 has in the short term impacted school budgets and school openings. At Prizmah, we use this data to inform the support and offerings we provide to schools. In the coming year, we plan to conduct additional research of current trends in development and enrollment.

https://prizmah.org/knowledge/resource/fall-2020-planning-second-pulse-survey-results

The Advice Booth: Admissions Programs During Covid

As the director of admissions at my school, I typically run recruitment events so that prospective families in the community can get to know our school. I’m looking for creative ideas to engage prospective families that go beyond a typical Zoom session, as we know that families have serious Zoom fatigue. What would you recommend?

Over the past few months, we’ve gathered a lot of great ideas for engaging prospective families in the era of Covid-19 from the cohort of schools in DSEE, the Day School Engagement and Enrollment initiative, and weekly check-in calls with admission directors.

Just as many schools are taking a hybrid approach, a mix of in-person and remote learning, consider a hybrid approach program. At Saul Mirowitz Jewish Community School in St. Louis, Director of Admissions and Marketing Patty Bloom ran an online STEAM Studio program in partnership with PJ Library. Patty prepared bags of supplies (including Mirowitz swag) and invited families to stop by the school to pick up their bags in advance of the virtual program. Patty shared that the pick-up allowed her to have one-on-one conversations with prospective parents, and even give some impromptu tours around the outside of school.

Another idea comes from SAR High School in Riverdale, New York. Director of Admissions Shifra Landowne is partnering with a current student to create an Instagram account that captures life at SAR, pre-COVID. Students will be asked to share video clips and photos from previous years that represent their high school experience. Parents and eighth graders will be invited to follow the account as a way to get a taste of the SAR experience.

Rabbi Yael Buechler at the Leffell School in Westchester, New York, ran a series of programs over the summer to engage families looking for

activities for their children who were stuck at home. One model that they experimented with was a buddy program, pairing up current middle school students with prospective pre-schoolers. The middle school students would read stories to their younger buddies once a week, giving parents a break and also providing young families with a glimpse into the community of Leffell students and their families.

We’ve heard lots of other great ideas, from renting an ice cream truck and handing out ice cream around the neighborhood to outdoor socially distanced programming in a school garden or apple orchard. Keep in mind that these types of initiatives can also be a part of a retention strategy, as a way to engage current families, and in particular any new families that enrolled in your school due to the pandemic. What’s most important in designing these programs is considering what the needs of families and students are and how you might address their needs, and meeting them where they are at, whether that’s on Instagram or at a local park.

Commentary: Day School Parenting Under Covid

It was my daughter’s birthday a few days ago. When she woke up, my daughter was so excited to see the decorations; my wife also surprised her by making crepes for breakfast (with fruit, whipped cream and nutella).

Then the Zoom calls started to happen. My daughter was pumped chatting with her swimming friends, and then jumped on another call with her school friends. Presents and signs started to show up on our front lawn.

A large group of our neighborhood friends planned a birthday drive-by. When we started to hear the beeping and cheering, we all ran to the front porch to see what was going on. You can see her face, pure joy.

Most of the day was filled with small acts done by other people for my daughter. Each one made the day special. But more importantly, each compassionate act did something much more powerful. It allowed her to see that even when life is crazy and unexpected, it is the people who can make it better. It is the people who build our hope through compassionate action.

I’ve seen this all over the world as we are faced with a pandemic. The stories are happening right now in front of us, the compassionate actions are starting to impact all of us, and empathy is needed now more than ever.

From “The Power of Compassionate Action” on A. J. Juliani’s blog

Amy D. Goldstein, Parent

Robert M. Beren Academy, Houston

When I recited Kaddish for my parents, I davened at our school with my daughter each weekday. Throughout their illnesses, we traveled between our home in Houston and my parents’ homes in Detroit, and my daughter was allowed to participate in classes online. During shiva for my father, I heard about hospital preparations for the imminent pandemic arrival. Shortly thereafter, the school closed in-person learning on a Friday and started remote learning the following Monday.

What surprised both my daughter and myself was her resilience as she thrived in this online environment. Her writing improved tremendously. She was able to sleep more, focus more and improve her skills. While she misses the social interaction, this tradeoff has been helpful to her as she prepares her college essays. Additionally, being homebound has sparked greater creativity and intellectual curiosity, leading her to read 17 classic books on her own this summer. Whatever happens this year, our school’s online delivery has enhanced my daughter’s education and developed skills that will help her succeed throughout her life.

Jessica Cohen Banish, Parent

Akiva School, Nashville

What do our children really need to be happy? Beyond basic necessities, teaching and showing our children kindness and appreciation—and encouraging them to do the same—matter most to their overall wellness. Mitzvahs for others and small acts of tzedakah that show thought and love are so important. Drawing a picture for a neighbor, checking in on seniors, dropping off cookies, driving by a friend’s house on their birthday or volunteering within the community are small acts that make a big difference. Small acts improve overall happiness for the giver and the receiver and teach compassion.

Our school does an outstanding job of supporting this value. Educators show love and appreciation to every child. They use positive reinforcement as a tool to guide students to make the right choices, and they lead by example. The school encourages students to create fundraising campaigns and food and supply drives to help those in need, and emphasizes the importance of empathy and being kind to one another.

It’s the small acts that make the biggest impact on our children now and on the adults that they will be become.

Rachel Harow, PTA Chair and Parent

Katz Hillel Day School, Boca Raton, Florida

My family was ill-prepared for the sudden shutdown of daily life as we knew it, but we initially welcomed it as a much-needed break. It gave us a chance to breathe, get to know each other, and reevaluate our priorities. While adjusting to life at home, we learned to appreciate how very blessed we are. However, the gaps in our lives rein- forced the importance of community and reminded us that maintaining connections is vital.

Without the myriad distractions of “normal” life, my children’s eyes were opened to those whose needs have been compounded by this pandemic. They stopped focusing (as much) on what they were missing and empathetically began to uplift others. Preparing sandwiches for the hungry, donating clothing for the needy, making masks for the vulnerable, and writing to the lonely gave expression to their compassion. The ability to have a positive effect on our community made a remarkable impact on all of us, and I am profoundly grateful.

In the Issue: Remodeling

If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

There is no gainsaying the challenges that schools have faced this year. Illness, tuition, expenses, technology, mental health… Each word conjures a thousand pictures of heroic efforts made across the school to support, adapt, persevere. No one has gone unscathed, and no scathe has gone unnoticed and unattended by school professionals.

Nevertheless, this issue of HaYidion provides ample testimony that Jewish day schools are not merely surviving and adjusting to difficult circumstances. Instead, over and over, we see schools overflowing with thoughtfulness and creativity. Like Picasso, schools are constantly drawing plans, changing shapes, inventing new plans over them, and living in the flow that this shifting situation requires. New teams—medical professionals, architects and engineers, tech specialists—suddenly arise to take a prominent place in the constellation of school stakeholders.

Heads are communicating with humor and transparency, reaching out regularly to hundreds in the community to let them know that they care. They admit to having a million answers and none at the same time. Teachers, at times daunted but unbowed, are proving again to be the true miracle-makers, having modified curricula, embraced myriad tech platforms, taught live and remote at once, zeroed in on each student’s strengths and needs, while infusing their classrooms whether in-person or remote with the passion and intelligence they bring to their subjects.

The articles in this issue demonstrate that, remarkably, day school stakeholders are continuing to dream about their schools, their community, and their craft—and doing so with more intensity and vibrancy than ever before. All of the training, the regular preparation, the professional development and investment in change that schools made before Covid are showing their value now palpably, “in the sight of all the people” (Exodus 19:11). Even as they work to create solutions to the challenges of today, they have an eye to the future, trying to anticipate which changes will bear fruit—which “castles in the air” may acquire a “foundation”— in a post-Covid world.

The first group of articles explores ways that our school leadership has shifted and seized opportunities. Adler and Perla present the new landscape of tuition plans that are changing the way that many schools are doing business. Falchuk describes new admissions strategies that her school has undertaken. Lorch examines whether prominent leadership theories have held up under Covid, while Grebenau relates how his work now has been guided by the theory of adaptive leadership. Maayan and Rubin share the lessons they drew from a previous crisis to succeed in this one, and Hartman and Friedman show how educational leaders can support teachers through techniques of reflective supervision.

Our school spread presents creative means that schools used to promote student collaboration despite remote learning. The second section discusses unprecedented forms of collaboration, both internally within school communities and externally with other schools. A series of short articles by Gold, Shulkind, and Feifel Mosbacher showcase new partnerships among heads in different cities. Freundel introduces a partnership among day school consultants organized by JEIC, and Hindin speaks to ways that federations can operate to keep schools strong and healthy. Michaelson and Lidsky demonstrate how the communities within schools have adapted and collaborated to achieve resilience, provide succor and forge unity.

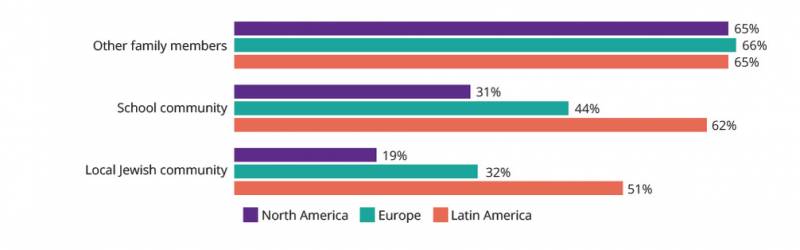

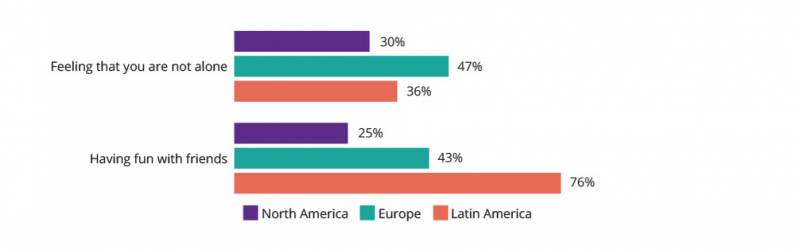

The final section looks at ways in which the “new normal” is impacting teaching and learning, school and home life. Hyman offers techniques for teachers to partner with parents in support of diverse learners through remote learning. Cohen provides recommendations for supporting parents, students, teachers and administrators to manage the enormous stresses on our lives today. Wolf gleans what we’ve learned about educational technology over the pandemic, and anticipates what could guide us toward the future. Rutner explores alternative assessment strategies that teachers can use, and Levingston presents how moral education looks radically different given current social upheavals. Taking a step back, Pomson and Aharon share research findings that contrast the purposes that day schools serve in their students’ lives, in North America versus other regions, and how that contrast is manifested during Covid.

May all the hard work that you and your colleagues are doing during this time both enable you to thrive now and establish foundations for success in years to come.

From the CEO: Scaling the Mountain Ahead

In the world of mountaineering, there are three rules: It’s always further than it looks. It’s always taller than it looks. And it’s always harder than it looks. I have never imagined being able to climb a mountain, an achievement I believe to be beyond my capabilities, my stamina and, to be honest, my vertigo. And yet there are many extraordinary people who scale the peaks, many of whom perhaps at one time felt as I do, as if such a challenge is beyond their reach.

Is grappling with Covid like climbing the proverbial mountain, farther, taller and harder in every dimension? If it is, then I am confident that leaders and educators in Jewish day schools and yeshivas are able mountaineers. They conquer the daily challenges and will emerge on the other side of this crisis stronger, prepared for a changed society, and able to demonstrate more than ever the value of a Jewish day school education. The Covid crisis unleashed creativity and innovation intrinsic to our schools. The immeasurable value of community, support for the whole student, and deeply ingrained Jewish values—all essential features of what our schools provide—are being recognized in new ways. Jewish day schools stand tall on every dimension.

I know that right now, teachers and school leaders may struggle to see the end of this arduous climb, and the daily struggle to fulfill a school’s mission can feel overwhelming and unending. Each day, I hear more examples of the courage, determination and inspiration of our educators, and I thank each and every one for your leadership and commitment to provide the very best experience for every student.

Yet to fulfill our schools’ true potential, we need to begin looking beyond the mountain directly in front of us and prepare for the next heights to be scaled. We must dare to imagine a future beyond Covid. As we begin to do so, how might we build on our experience in crisis to inspire what might come next?

A recent McKinsey report on the future of the K-12 education system argues that “reimagining education after the Covid-19 crisis involves recommitting to what we know works and reshaping for a better future.” A central feature of recommitting to what works is a focus on people, delivering the core skills and instruction each student needs. And reshaping, according to McKinsey, includes harnessing technology to improve access and quality, supporting children holistically, as well as rethinking school structures.

The research suggests that Covid has not completely disrupted the core educational exchange: “While greater use of technology in education may be inevitable, technology will never replace a great teacher. In fact, a single teacher can change a student’s trajectory.”

A successful future, therefore, starts with people. Building on what Prizmah and many others do to deepen talent in Jewish education, there is more we can and should do together, to recruit, motivate, support, inspire and retain the best educators, invest in new models of training and development, and make roles in professional and lay leadership fulfilling, manageable and sustainable. And we need to focus on how to nurture the next generation, in Judaics and Hebrew, in general studies and in leadership.

Recommitting to what works with a focus on people needs to be blended with a commitment “to move beyond existing approaches to embrace more radical innovation.” Technology is, by definition, central to radical change; the challenge is not “just to adopt new technologies but also to incorporate them in ways that improve access and quality.” Building on our current experiences deploying diverse educational technologies, we are already finding ways to strengthen the quality of learning, provide online access to teachers and pedagogical experiences previously out of reach, and to offer greater and more effective differentiation to advance and include every learner, no matter how their learning styles and needs differ.

“Reshaping for a better future” also means “supporting children holistically. … Educators play a critical role in helping children learn how to become effective citizens, parents, workers and custodians of the planet.” Here we have the opportunity to invest in building on day schools’ existing strength in serving the whole child. Additionally, the core values of community and fundamentals of Judaism position day schools to excel in a world that needs each individual to discover his/her unique strengths and build connections for the greater good.

A final challenge as we reimagine education after Covid-19 is to “rethink school structures.” The world of business is coming to terms with the realization that Covid-19 has changed how people behave across every aspect of their lives. This matters to us as we create or adapt systems to address our current and future students and families. The possibilities are manyfold, from physical classroom transformations, to alternative tuition models that make schools more affordable and sustainable, to ways in which we might reconfigure the mix of schools in our communities to meet the needs of the rising generation and to address significant demographic changes.

We are at the beginning of exploring what might be possible, and I know that it may seem impossible right now to contemplate these questions in the midst of what each school faces day to day. When one mountain is facing you, it is hard to imagine the next one. At Prizmah, we are with you in tackling the immediate questions, seeking to support your climb so that we may all, God willing, come through this terrible period. And we are preparing to chart the journey forward with you, into our next, vibrant chapter in Jewish day school life.

From the Board: Empowering Boards to Step up

I have been so impressed with the determination, resilience and creativity of our day school community in attacking the challenge of returning to in-person instruction and/or providing the best-possible virtual learning. And I couldn’t be prouder of the myriad ways that Prizmah’s professional staff has enabled schools to cope with, and even grow from, the Covid experience.

I would like to focus on the unique impact that the crisis has had on day school boards and offer three ways we can capitalize on the operating mode in this environment to improve board performance during the pandemic and beyond.

1 It is often said that we must never let a good crisis go to waste. The simple reality is that a difficult operating environment energizes lay leaders to step up to the plate. But it does not happen by itself. The board chair and professional leadership must ensure that the board has sufficient information and suggested modes of involvement that are both achievable and impactful. If done well, lay leaders walk away from the experience more energized and engaged, and with a deeper relationship with the institution and its professional staff.

As with so many other institutions birthed and nurtured by The AVI CHAI Foundation, its sunset left a major gap in Prizmah’s operating budget. Notwithstanding a long notice

period and transition support from the Foundation, replacing millions of dollars in philanthropic support was, and remains, a gargantuan task. However, everyone in the organization assumed responsibility. From the board side, lay leaders became far more familiar with the organization’s operating environment and costs, ramped up their involvement in development efforts and, in almost every case, increased their own board giving. Today, long after this crisis, our financial stability is very much a product of the changed role of the board in both giving and development.

2 The current pandemic has upended school operations, to put it mildly. All sorts of decisions must be made, often with extreme time pressure. The traditional pace and timing of board

involvement simply does not suffice for the current environment. While some schools might respond to the pace of decisions by a diminishment of the board’s role in issues that would normally be in its domain, bypassing the critical governance role that boards play and, perhaps more importantly, leaving the school without the vital buy-in and support of its board weakens the organization and detracts from the critical partnership between the professionals and the board.

Devising methods of board communication that clearly articulate potential avenues of approach, with a detailed listing of the pros and cons of each option, allows a board to quickly make difficult decisions. Figuring out those issues that need, or can benefit from, board engagement ensures that limited board time is used in an effective fashion and that board members feel that their involvement affects the reality on the ground and utilizes the talents that they bring to the boardroom table.

3 When board decisions are made and shared with the broader school community, there is often a torrent of questions and comments from community members—especially in the current environment, where everyone seems to have absolute and definitive views on the proper course of action for the school. At day schools, perhaps because the stakes are so high—nothing less than the Jewish future—everyone cares a great deal.

One of the most effective board functions is the presentation and explanation of decisions made by the board. While parents and other stakeholders may disagree with a decision, they will accept it far more readily if they understand how the decision was made, who was involved in the decision-making process, and the factors and alternatives that were considered. Board members can and should be equipped to fulfill this role. Big decisions should be accompanied by a clear set of talking points, and board members must speak with one voice. Board members can even practice how to present decisions in role-playing scenarios within the safe space of a board meeting.

Emboldened by their commitment to the school’s mission and purpose, board members who are properly engaged in decision- making and communication will meaningfully assist school leadership in navigating the challenges of Covid-19. Focusing on these processes will improve board utilization, effectiveness and satisfaction during, and hopefully long after, the Covid-19 crisis.

Good News on Alternative Tuition Models

The Covid pandemic has had a significant impact on Jewish day schools, increasing enrollment at some, forcing others into a virtual existence. It has also caused many schools to reexamine their tuition and fee structures.

About a decade ago, alternative tuition programs began to proliferate as individual schools, federations and donors realized that new, more creative approaches to tuition setting were necessary to underscore and demonstrate a clear commitment to day school affordability. Many of these first-generation tuition programs were based on the hypothesis that a lower tuition for targeted segments of a school population would lead to improvements in both recruitment and retention. While a handful of individual schools and federations introduced programs that significantly lowered tuition for all families, the majority of alternative tuition programs targeted specific cohorts of families through a needs-based approach.

FIRST-GENERATION PROGRAMS

Three years ago, Prizmah and Measuring Success undertook a study of these programs. The most common programs we examined included middle-income affordability programs, including income- cap programs; flexible or indexed tuition programs; non-needs-based tuition- reduction programs, and discounts for Jewish communal professionals. The primary purpose of the study was to assess the efficacy of these early programs in recruiting and retaining 10 more day school families. While the study results seemed to indicate that communally designed, donor-funded programs performed better than programs that were school-designed and lacked donor support, the results of the study were generally inconclusive and failed to establish causality between tuition reductions and enrollment growth.

One of the explanations for the study’s inconclusive findings was a lack of intentionality in program implementation. Our research found that many of the first generation programs were designed without clear data analysis, and sometimes without buy-in from the school’s leadership. Some of the programs were created solely in response to a donor’s wishes and were discontinued as soon as the donor became disenchanted with the program. Other programs lacked donor support altogether and were undertaken by schools with the mistaken belief that a rising enrollment would sustain the program financially. Such programs were often dropped within a year or two of their launch.

SECOND-GENERATION PROGRAMS

The design of more recent, second- generation tuition programs suggests that schools and communities are materially adapting their approach. These programs are notable for their embrace of data.

This includes both local and national data related to family income levels and scholarship, local and national data related to school satisfaction among existing parents, and local and national surveys related to perceptions of day schools. Second-generation programs are more likely to be backed by significant multiyear philanthropic support to allow time for the programs to succeed and for modifications to be made, if necessary. Alternative tuition programs at both San Diego Jewish Academy (SDJA) and Westchester Day School (WDS) are examples of this new, data-driven approach.

SDJA’s Open Door tuition program offers significant discounts for new families who enroll their children in entry-level grades: kindergarten, sixth and ninth grades. SDJA conducted research and analyzed extensive family income data before launching their highly successful program. It commissioned an independent research firm to survey middle-income families in the San Diego area on their views of Jewish day school and tuition prices. The survey indicated that more than 1,100 Jewish families with school- age children in San Diego would consider a Jewish day school if its tuition was between $10,000 and $15,000. Based on its findings, SJDA lowered its tuition in entry-level grades to the mid-level of this range for new families. Three years in, the school credits the donor-funded program for its record enrollment.

WDS began to experiment with alternative tuition programs nearly a decade ago when it lowered tuition prices in some lower grades in an attempt to accelerate enrollment growth. Later on, the school created an income-based tuition cap program based on a more sophisticated, data-driven approach. Through the program, middle-income families can apply for up to 40% off full tuition based on a simple application. The school even developed an online tuition calculator so that families could easily project their tuition obligation with a few inputs and the click of a button.

Three years ago, TannenbaumCHAT, a community high school in Toronto, had two campuses and charged a tuition in excess of $28,000. The school was experiencing significant declines in enrollment and undertook a detailed survey of current and prospective day school families to understand the role that the school’s tuition price was playing in their enrollment decisions. The survey results suggested that many families would be interested in enrolling their children if tuition prices were more in line with middle school tuitions they were used to paying.

Based on this data, the high school announced the closing of its northern campus and lowered tuition prices at its southern campus by nearly 40%. The federation played a pivotal role in the program’s design and helped the school secure a multiyear, multimillion dollar gift to ensure the school’s financial stability. Enrollment at the school’s south campus has increased dramatically (over 25%) since the program’s inception, and the school has retained the overwhelming majority of its north campus students.

Where first-generation programs often took a needs-based approach to tuition discounts, many of the latest programs have lowered tuition either in entry-level grades or for all families, regardless of need. As an example, New England Jewish Academy (NEJA), in West Hartford, Connecticut, recently lowered its tuition for all families. While it is too early to determine the success of the effort, the school reports that early enrollment results are promising. Like other schools that have lowered their tuitions, NEJA hopes that lower tuition will enable the school to be more attractive to both existing and prospective families. They also anticipate that wealthier families will be more likely to make voluntary, tax- deductible contributions if their obligatory tuition is lowered.

It is also worth noting that the collection and analysis of additional data and ongoing donor support can lead to adaptations in existing tuition programs. Nearly a decade ago, Kadima Day School in Los Angeles announced a significantly reduced tuition level for first-time families to the school. A strong backlash from existing families who were ineligible for the lower tuition level ensued. Based on extensive survey data, the school discontinued the original program and worked with its initial donor to create a revised program that dramatically lowered tuition levels for all families. The school reports two years of consistent enrollment growth, a trend it attributes in large part to its revised, donor-funded program.

COMMUNICATIONS

Alongside the improved programmatic elements in recent alternative tuition programs, there is a critical element to success that should not be overlooked: messaging. How a school or community messages its tuition program speaks volumes about its principles and values and should align with its stated mission. Alternative tuition models afford schools an opportunity to articulate these values and actualize their mission.

Consider the language used by the Greene Hill School in Brooklyn to describe its sliding-scale tuition program and how it connects directly to the school’s mission: A sliding scale tuition means that families pay the tuition that is appropriate for their family’s income and financial resources.

Practically, Greene Hill has established seven different tuition tiers, and a financial assessment will determine which tier is appropriate for each family.

An independent private school, Greene Hill is committed to diversity, and the sliding scale is one of the ways that we live our mission.

The Solomon Schechter of Greater Boston uses a description of its iCap tuition program to articulate two critical and complementary values: Tuition should be predictable in order to encourage parents to confidently enroll all their children; parents must be prepared to make a meaningful contribution toward tuition.

Schechter is committed to partnering with families who are ready to make a meaningful contribution toward tuition in accordance with their financial means... ICap Tuition Program is designed to enable families with children in kindergarten through grade 8 to anticipate their maximum future tuition obligation and confidently enroll their children at Schechter year after year, regardless of the number of children in each family.

The Hannah Senesh School in Brooklyn uses messaging in its strategic plan to inform parents of its values regarding school sustainability and parent affordability:

We will analyze our various and potential income streams, and research and review tuition models, in order to select and implement the options that will likely best achieve our goals of generating sufficient income while easing the burden on our parents.

The statements on these school websites are examples of clear and transparent messaging about tuition assistance to the potential customer. They express the school’s commitment as well the range of programs offered in an effort to find the best fit for each family.

In summary, many second-generation alternative tuition programs have benefited from greater intentionality in their program design and a focus on data-driven analysis. Partnerships with local federations and donors who make multiyear financial commitments have ensured that programs are set up for success. Recent results have been promising, and the field needs to carefully consider the scalability and applicability of these programs. Messaging these programs in a way that conveys a school’s core values and connects back to its mission is critical.

Prizmah is conducting more research aimed at better establishing causality between lower tuition prices and student recruitment and retention. We also plan to convene school and communal leaders, both lay and professional, to share our research and to help us plan a series of programs and initiatives related to tuition and affordability.

We look forward to sharing our research findings and to unveiling new initiatives soon. Both efforts will enable Prizmah and the field to carefully consider the scalability and applicability of these programs in the future.

The Value of Flexibility in a Pandemic: Recruitment and Retention

In the cycle of Jewish day school admissions offices, summer and fall are very busy times for team building, strategizing and planning. It takes an enormous group effort to coordinate and implement a successful admissions campaign, and each year we infuse new vision and ideas into our process. However, this year is like none before, and while the methodology is the same, the delivery is different. There are no balloon bunches being designed for open houses, nor in-person tours and interviews.

This year, the stakes are even higher to bring in a full class, and our retention goals are more important. At Gann Academy, we have fostered a high retention rate and are cultivating a strong recruitment season. This success has been achieved through a new communication strategy, expanding financial aid programs and dollar amounts, re-structuring our educational model, and varying our admissions process.

We began with an inside-out approach to our community, initially focusing on the retention of current families. As main stakeholders, current families deserve transparency in communication. Messaging was, and continues to be clear, concise and prompt. In addition to town hall Zoom meetings over the summer, we sent frequent communications to keep our families updated on our thoughts and planning. We realized that parents appreciated our emails in their inboxes, and while there is such a thing as too much communication, we settled on a flow and volume of emails that seemed right. This clear communication strategy proved beneficial in terms of retention; we knew what families needed from us in order to continue a Gann education, and we were able to provide that support.

For example, it became abundantly clear that families were worried about affording our education. In partnership with our board of trustees, we created a new campaign, “Gann Cares,” built as a Covid relief fund, to support both new and returning families. Additionally, we were able to allocate an extra $1,000,000 in financial aid, and more than 30 families were retained as a direct result of our Gann Cares campaign.

We next focused on re-opening to in-person learning, not only to secure retention but also to increase recruitment prospects. Our school day had always been long, with eight academic classes, prayer and extracurriculars; students stayed on campus from 8 am to 5 pm. With a shift to hybrid learning, the possibility of having to go fully remote at any time, and feedback from our stakeholders, we knew we needed to change our program. After research and consultation with academic leaders across the country, we chose a two-semester model, with four academic blocks each semester. This approach gave us the ability to work intensively in a subject, but also provided flexibility for our learners.

Classes last one hour and meet four days a week. On Fridays, we are fully remote, and students have the opportunity to work with teachers as needed on independent study. For students who are unable to attend in person, we created an online option which included academic classes, minyanim, sports, arts and wellness.

This holistic approach to academics and safe re-entry to in-person learning has positively impacted our recruitment and retention. Current families are thrilled to know their children will continue a high-quality education with physical and mental health supports, and prospective families are beyond excited to have a school committed to in-person learning. Committing to in-person learning alone earned more than 12 late applicants.

The continuation of our robust in- person academics, vibrant student and Jewish life, and strong learning supports ensured a successful admissions yield. Families outside of Gann suddenly found themselves without classes, without friends for their children, and without clear communication from their school systems. Suddenly, we had an influx of new families looking to come to Gann, as well as new families with financial concerns. To balance this influx and promote recruitment, we again relied on flexibility.

In previous years, we were not able to offer late admits financial aid. This policy presented a barrier for families who were off-sync with the traditional admissions cycle; changing it has rolled out the welcome mat for the high number of late applicants. Concluding that there are many other ways to assess a student, and understanding that testing is less accessible now, our admissions team decided to make Gann SSAT-optional. We are now using the “character snapshot,” affiliated with the SSAT through the Enrollment Management Association, as part of our process.

As we look toward our upcoming admissions cycle, we are retaining the beneficial changes implemented last spring and continue to be open to veering away from tradition. Like most schools this year, we are not allowing visitors to our campus. A critical part of our admissions cycle is our large,

in-person open house in the fall. Now we are creating a new way to showcase our school, involving virtual tours and interviews, engaging online information sessions, and more nuanced and individualized outreach. We are also continuing to partner with our feeder schools on outreach programming. The evolving nature of the Covid-19 pandemic requires recruitment efforts to be digital but also interactive, nimble but focused, and above all creative.

Reopening in a pandemic has required learning. We have learned the value of being flexible and are reminded each day of the importance of proactive planning and communication. This learning has proven its worth; our successful programs, both in person and remote, have become so popular that we have an overall retention of 98%, a waiting list for grades 9-11, and interest in providing an online learning program for students outside of Gann. Though the flexibility required of students, faculty and staff is intensive and ongoing, our school has proven that both retainment and recruitment are indeed possible during a pandemic. We will continue to be flexible in our approach, our pedagogy and our operations as we anticipate the shift back to post-pandemic school.

Leadership Lessons in the Time of Corona: Practice and Theory

The heroic stories of Jewish school leaders who transformed their schools in the face of a pandemic of daunting scale are legion. Principals and curriculum coordinators spearheaded and supported their faculties in overnight transitions from in-person learning to remote learning and in subsequent refinements of online teaching practices. Board leaders and directors of finance responded to parents’ financial distress with creativity and compassion and scrambled to access newly available financial and material resources. Heads of school formed task forces, advisory groups, and response teams, collected and analyzed survey data, and expanded their communication with various constituencies, constructing web pages, convening town hall meetings, and increasing the frequency of their email and social media blasts.

Participation spiked in school leader discussion groups and listservs (many sponsored by Prizmah), as well as in webinars with experts in fields that had previously been peripheral to school operations, such as public health, remote learning and architectural design. Schools were not paralyzed by the magnitude of the challenge; on the contrary, they sprang into action and engaged in high- quality leadership activities of nearly every imaginable kind.

One notable exception comes to mind: the flurry of activity tended not to be grounded—at least not explicitly—in theories of leadership and change in schools and organizations, theories that might have served as obvious go-to resources for school leaders during a challenge of this scope and complexity, such as adaptive leadership (Ron Heifetz and Marty Linsky), systems thinking (Peter Senge) and good-to-greatness (Jim Collins).

In keeping with the classical rabbinic tradition of publicly confessing one’s shortcomings before the congregation, the next part of this article is written in the first person singular. As I sought to respond to an emergency that challenged nearly every one of my operational assumptions, from teaching and learning to school finance to community and connection to mental and physical health, it never occurred to me to revisit or mine the literature on leadership and change that I had studied and taught extensively in graduate education courses and in day school leadership training programs.

This lack of appeal to theory flies in the face of one of the maxims of social science: “There is nothing as practical as a good theory” (Kurt Lewin). How are we to make sense of this disconnect? What can explain my seemingly counterintuitive flight from theory at precisely the moment when it might have proven most useful?

HYPOTHESIS #1: THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CRISIS RESPONSE

In the throes of a crisis, theory may be an unaffordable luxury. An individual faced with a life-or-death threat casts about for solutions, finds none, and is therefore at a loss as to how to cope with it. As Abraham Maslow wrote,

For the man who is extremely and dangerously hungry, no other interests exist but food. He dreams food, he remembers food, he thinks about food, he emotes only about food, he perceives only food and he wants only food… Anything else will be defined as unimportant. Freedom, love, community feeling, respect, philosophy, may all be waved aside as fripperies which are useless since they fail to fill the stomach.

For Jewish day schools, the onset of Covid-19 produced a series of existential crises: how to remain a school without a physical space called school; how to conduct classes without classrooms; how to respond with compassion and pragmatism to the distress, economic and otherwise, of families; how to survive a massive loss of tuition and fundraising income; how to meet the learning needs of children when nearly every strategy known to educators was unavailable. Overnight, I found myself in an epic struggle for my school’s continuing relevance, if not its very survival. In such circumstances, perhaps expecting myself to contemplate theories of leadership and derive lessons for my practice is tantamount to expecting a starving person to write poetry.

HYPOTHESIS #2: THE LIMITS OF LEADERSHIP THEORY

The leadership literature may not be well suited to moments of crisis. Though the various theories purport to provide ways of thinking and acting that make organizations more nimble and better able to withstand threats and transform themselves in crises, the strategies that they delineate purport to develop the capacity in advance that will enable the organization to thrive later, when crisis strikes.

For example, Collins’ timeless prescriptions are all preconditions to achieving greatness. Cultivating Level 5 leadership (the CEO combining humility and will), getting the right people on the bus, and rethinking the organization’s hedgehog concept (an understanding of what the organization can be the best in the world at) are critical factors in the organization’s ability to weather a crisis and come through it stronger than ever. They are not concepts to first explore when the crisis hits.

Similarly, Senge’s key disciplines are ways of transforming organizations into learning organizations; they are not guidelines for how to respond to profound crises. Personal mastery, building shared vision, team learning and systems thinking are elements of a framework for preparing to deal with the dynamic complexity of situations and forecasting the effects of interventions. With the possible exception of the concept of leverage (a small, non-obvious “change which—with a minimum of effort—would lead to lasting, significant improvement” systemwide), they are not strategies for survival in an existential crisis.

Heifetz and Linsky offer a framework that is directed inward at organizational challenges, and less toward external existential risks that are much larger than the organization. Alternating between the dance floor and the balcony (being both a participant and an observer), cooking the conflict (applying moderate pressure for change) and creating productive disequilibrium (motivating people by focusing on tough issues while reducing anxiety and turmoil) make sense as strategies to awaken an organization to the need for wrenching transformation. They are not well suited to crises that are so threatening that they eclipse all other activities or challenges.

Why, in the turbulence of a once- in-a-century pandemic, did I not consciously step back, take perspective and contemplate the relevant lessons learned from leadership theory and their immediate implications for my daily practice? On the one hand, the leadership lessons were mismatched to the rhythms of a dynamic, fast-paced crisis. On the other hand, it was too late. If I had not yet learned the lessons, synthesized them into my practice and begun seamlessly applying them to the issues and decisions at hand, first developing plans to roll them out in the midst of the pandemic would likely have proven counterproductive.

HYPOTHESIS #3: THEORY IN PRACTICE

Perhaps many of the actions that Jewish day school leaders took in response to the Covid crisis did benefit from a theoretical framework, just not explicitly so. Chris Argyris and Donald Schon explain that professionals have what they call theories of practice, which are often not clearly articulated, but rather become visible through the actions they adopt and the explanations or predictions they have in mind to justify their choices of actions. The measure of effective professional practice, they claim, is the extent to which these theories of practice can subsequently be publicly espoused, challenged and tested.

For example, when heads of school recruited medical advisory groups, legal advisers and human relations consultants to support them in their planning and decision making, many of them were acting on one of Collins’ key findings: the importance of getting the right people on the bus. By preparing for multiple scenarios and implementing them as conditions dictated, they were following Heifetz and Linsky’s advice to observe, interpret, intervene and repeat. The feedback loops that they established with their schools’ varied constituencies— faculty, staff, parents, students, donors—reflected the understandings about shared vision, team learning and transparency that they may have derived from Senge. Whether intentionally or not, many of their actions, if not most, reflected key insights drawn from the leadership theories that they had studied at earlier stages of their careers, without which their actions might well have proven less effective.

TACHEL SHANAH UVIRCHOTEHA — COUNTING OUR BLESSINGS

Another school year, and a new Jewish year, 5781, have begun in the shadow of corona. After the strangest, most disorienting half year school leaders have ever lived through, they are prepared for the worst and hoping for the best.

Among the blessings we should count are the lessons our leaders have learned that raise their sights, inspire them to meet new challenges resourcefully, and embolden them to take courageous and incisive action. May our blessings this year be as plentiful as the seeds of a pomegranate.

WORKS DISCUSSED

Argyris, C. and D. Schon. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness.

Collins, J. Good to Great and the Social Sectors.

Heifetz, R. and M. Linsky. “A Survival Guide for Leaders.” Harvard Business Review, June 2002.

Maslow, A. H. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychology Review, 1943.

Senge, P. M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

Leveraging Covid: Adapting to Thrive

Back when the word “corona” evoked an image of an ice-cold beer, the concept of adaptive leadership was not on the front burner for most schools. Adaptive leadership enables organizations to identify changes needed to move forward guided by agreed-upon values. Thanks to its focus on leading in dynamic systems, however, it is especially applicable to this uncertain time of ongoing change.

In the midst of the coronavirus, the speed of change in our schools has accelerated to an unhealthy hurtle, and adaptive leadership is more important than ever. The challenge before us as school leaders is being able to turn leading through Covid-19 into an opportunity to learn new leadership skills that will help us to better administer our schools regardless of the specific challenges and contexts that are down the road.

ADAPTIVE VS. TECHNICAL

Adaptive leadership distinguishes two types of challenges: adaptive and technical. A technical challenge can be very complex, but has a clear solution. A playbook can be used to react to the challenge successfully, and there is a known goal where we want to end up. Replacing a faulty heart valve during cardiac surgery is a complex technical challenge. There is significant room for error, and it is tough work, but the technique needed, and the goal, are both quite clear.

An adaptive challenge, on the other hand, is an enigma of conflicting values where the direction and the path to achieve the goal are unclear. Adaptive challenges pit some of our deepest-held convictions against one another and require a specific type of leadership to move forward. This category has captured much of our work for the past months, as our most cherished values of pedagogy, safety and community have been in constant conflict and required painful concessions.

DIAGNOSING

Adaptive leadership asks leaders to distribute not just work but authority. It requires leaders to engage their staff in the work of examining and debating conflicting values on the way to changing hearts and minds. The goal of adaptive leadership is to identify the changes, however painful, that are needed for the future health of the organization. This requires an experimental mindframe and cycles of observation, interpretation and intervention. When diagnosing a problem, it is critical to stay low on the ladder of inference and hold numerous potential interpretations at once, rather than quickly identifying the cause of an issue.

Over the summer, we experienced a series of teachers resigning in quick succession. There was clearly an element of this trend that was related to anxiety over Covid. Although some quickly wrote it off as just “Covid makes people crazy,” others on the leadership team cautioned that we need to make sure there isn’t anything else going that needs to be understood. We stayed low on the ladder of inference and focused on the rate of faculty turnover, even given the unusual context. The fact that more than one or two teachers were actively looking for other opportunities was something we needed to understand, and we needed to be open to multiple possible explanations. Having our human resource professional perform exit interviews with the exiting staff allowed us some insight into how other changes in our schedule and pay structure might have played a role. Being open to other interpretations allowed us to continue to search for this feedback, which might otherwise have been overlooked.

CALIBRATING DISCOMFORT

One of the central ideas of adaptive leadership is calibrating discomfort. When there are conflicting values and adaptive challenges, people will feel a sense of disequilibrium. The goal is to remain in the zone of disequilibrium long enough to harness the conflict and discomfort in order to truly unearth what values may be in conflict and the best direction for the future. However, the leader must make sure that they do not remain in disequilibrium so long that the level of anxiety and discomfort is too much for the teachers to tolerate. If we leave the zone of disequilibrium too early, the organization has avoided the tough work that will result in discovering solutions to adaptive problems. Staying too long in this zone may cause the leader to damage trust and relationships with staff.

Recently, in a meeting with teachers as we planned programming for this challenging year, I harnessed discomfort when I did not allow us to go to the quick solution of using our same recipe for programming and just subdividing the student body into pods. I had to repeatedly bring us back

to the idea that we were thinking out of the box to come up with an idea that we would feel good about continuing even after Covid. It would have been far more comfortable to move on and solve this issue with some of the initial suggestions, but digging into the disequilibrium netted a more creative and satisfying solution.

GETTING ON THE BALCONY

Another important aspect of adaptive leadership is the concept of “getting on the balcony.” In my own research on new principals in Jewish day schools, one participant referred to this as “time in the shade.” This meant taking the time to get out of the hustle and bustle of the school day and reflecting on the general picture of the school as well as on your own part in the system.

This work can’t only be relegated to the summer, but summer is a good time to intentionally begin this process with other administrators and set aside time during the year to continue the process.

I have seen a number of schools have offsite meetings for strategic planning, including for staffing decisions or creating the schedule. This same approach can be used for having regular balcony meetings or balcony moments to reflect on the overall picture of the school.

CHALLENGES TO ADAPTIVE LEADERSHIP

The benefits of successful adaptive leadership are a culture aligned with the goals and values of the institution and the agility to continue to make changes as needed. I’d like to conclude this article by discussing one area of challenge to this type of leadership: discomfort—one’s own discomfort and the discomfort of others. Heifetz, Grashow and Linsky speak about the fact that adaptive leadership means intentionally disappointing people who confer power on you. In our schools, both our teachers and our lay leadership frequently want us to focus on fixing what is currently not working well. Taking time away from the present concerns to deal with the culture and values conflicts is frequently not applauded and must be continually justified to these constituencies.

This reality is paralleled by our own discomfort in dealing with adaptive challenges. During the past months, I have found myself drawn to some of the more mundane tasks of administration even when there were other important priorities for the school. As I reflected on my preoccupation with more technical challenges, I realized that school leadership had for many months been a steady stream of adaptive challenges. Adaptive leadership means that we can’t really control (or even predict) the outcome of how a challenge will be dealt with, and that is scary. The more comfortable, technical challenges of school administration were oases of control for me, and I reveled in them.

When we embark on our own pursuit of adaptive leadership, we must be mindful that we too may be uncomfortable in this space and would also like to spend more time just putting out fires and making things better. To deal with adaptive challenges, we must allow ourselves the space to get up on the balcony and spend the time diagnosing and strategizing in a way that is future-looking, fighting the all-consuming needs of the present on behalf of the uncertain but nonetheless inevitable road ahead.

Drawing Strength from Prior Crises

Winston Churchill once said, ““Never let a good crisis go to waste.” We who work in the Jewish day school world are familiar with crises, both large and small. All of them offer opportunities to learn. Our particular crisis a decade ago has made us stronger, more resilient and better equipped to learn, reflect and innovate in our day school in this unprecedented time of Covid-19.

The Saul Mirowitz Jewish Community School in St. Louis was formed in 2012, the only known successful merger of a Reform and a Conservative day school. The new community school was created on the heels of a recession, over a two-year period, though a process that was excruciating, but also rich with learning.

Initial exploratory discussions about sharing office software and music teachers grew into conversations about bigger dreams: merging. One school had a new building, while the other leased space in a neglected temple education wing. One school’s head wasn’t continuing, whereas the other had a committed and respected leader at the helm.

Negotiations surged forward, then slammed into resistance. Both schools walked away at one point. Boards and staff struggled with deciding how we would eat, how we would pray, how we would teach Judaics to a pluralistic community. We couldn’t envision how everything we would lose could bring about something greater than the sum of its parts.

As the board president and head of school for one of the schools, we were catapulted into a world in which we had little experience. It was a 24-month roller coaster ride of rapid change, vocal and impassioned opinions from board members, faculty, rabbis, community stakeholders and parents. Fear, stress and trepidation about what we might be losing clouded our ability to identify the opportunities before us. It was hard to envision the future when we were facing our natural reaction to transformational change.

Nonetheless, we were exhilarated by the enormous potential of this new vision. The promise of a combined K-8 community school, with newly crafted mission and values, many more children and an unwavering commitment to excellence pushed us to persevere. Ultimately, with a strong board-head relationship, boards that ultimately looked at the big picture, and community leaders and donors who invested in the dream, the Saul Mirowitz Jewish Community School was born.

Several key ingredients made this possible. We sought out advice from others: federation leaders, merger experts, financial gurus, day school veterans in other cities, PEJE, NAIS and the best independent school leaders. Both boards weighed the pros and cons, and made brave decisions based on what was best for the children and the community.

We engaged in frequent communication with key constituents, especially parents. We listened. We shared carefully crafted information at key points. We surveyed, held coffees and town halls. We asked for feedback. We made mistakes along the way but absorbed, adjusted and advanced. There were arguments; tempers flared and coalitions formed; people mourned and resisted. Ultimately everyone awakened to the realization that the combined school was a much better place for our children.

Which leads us to the pandemic. Who could have possibly prepared for a pandemic and the way it would affect our students, teachers, board and community? Little did we realize how deeply our experience managing transformational change during the merger would impact the strength with which we navigated the uncharted waters of 2020.

We had experienced fear of the unknown and uncertainty about how long the crisis would last. We had learned to shut out the noise and put excellence for students first. We had sought out and applied the best advice from experts in the field, from board members and community leaders. We had leaned on the board-head partnership and supported each other once critical decisions were made.

So it turned out we were more prepared than we realized. We learned more than we thought and were able to call upon that experience, reflect on how we could apply a past lesson to the pandemic, and innovate.

HERE ARE THE LESSONS OF OUR TWIN EXPERIENCES:

Having gone through a crisis made us more prepared to manage transformational change. We made decisions on the fly, with good but often incomplete data. Yes, we made mistakes, but acknowledged them and kept moving forward toward our goal.

Steady and strong is vital (even when you’re not feeling it inside). The community trusted our commitment to making things right for the children of Mirowitz.

Seek out the gift of wisdom and experience from experts. We couldn’t do this alone. Our tagline should be, “Surround yourself with people smarter than you.” We gathered expert medical advisors and sought wisdom from board members on legal and organizational decision making. Our money has never been better spent on membership in Prizmah, NAIS, ISACS, DSLTI and others.

Listen, listen, listen. We’re going through a time of high anxiety, enormous uncertainty. People are nervous: parents, students, faculty, board. Acknowledge that anxiety, be kind and flexible whenever possible. Remind people of our ultimate shared goals: academic excellence, health and well- being of our students and teachers. Reassure that we will all get through this.

Change is hard; be sure to mourn what once was. But also celebrate what you’ve achieved that you couldn’t have imagined: new and rapid proficiency of technology; a quick pivot to remote schooling, a “Gala in the Cloud,” heightened partnership between board and head of school; launching a remote camp led by our young adult alums.

All this allowed Mirowitz to resume five day a week in-person school this fall. We are adhering closely to all CDC, state and county guidelines. We keep health and safety foremost in everything we do. And we continue to listen, learn, adjust and improve. It’s our fervent belief that going through a different but in many ways similar experience like the merger gave us the resiliency and confidence to come out stronger and better.

Supportive Supervision

Early childhood centers that have been reopening since early summer have a word of warning for schools: Don’t forget to make time for supportive supervision.

More than ever, educators isolated in their classrooms or behind their laptops need support. The early childhood field has a unique model of supervision, rooted in relationships and collaboration, that day schools could implement to their benefit. This article will demonstrate how the model functions and will argue that the unique benefits of reflective supervision are tailor-made for our time.

PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Reflective supervision developed in the field of infant mental health and is a kindred spirit to Parker Palmer’s The Courage to Teach. Just as Palmer instructs that teachers project the condition of their own souls onto their students, this model invites teachers to work with their supervisors to “hold a mirror to the soul.” Through entering what Palmer calls the “tangles of teaching” with a supervisor, the teacher is strengthened and brings that wholeness to his or her work with students.