From the Editor: Educational Innovation

The old will be renewed, and the new will be sanctified. - Avraham Kook, Igrot HaRa’ayah 164

This famous expression of Harav Kook, cited in this issue, would make a perfect mission statement for the field of Jewish day schools. It captures the magnificent, heroic efforts the teachers in our schools make every day. They expertly choose from our ancient writings and traditions, endowing students with the skills they need to read, understand and interpret them, giving students a platform to articulate their thoughts and, in the process, develop self-understanding as old-new, 21st century Jews. They also fearlessly incorporate the new, in the form of new thinkers and artists or new technological platforms, while helping students elevate the new, and use new media selectively, wisely, to find the wheat and discard the chaff. And that elevation takes place largely through the guidance and insight derived from our ancient wisdom.

The articles in this issue represent the balance between the old and new, sacred and profane embodied in Jewish history. The issue tells the story of the drive for innovation, an imperative in modern education that has gained strength on theoretical and practical levels in recent decades. It features efforts to learn from, adopt and adapt innovative programs and pedagogies from the larger educational universe. However, even as they adjust to shifting times, some authors advise caution, patience and planning around such changes. They observe that innovation often requires an enormous investment of time, people, money and more to achieve lasting success, and that sometimes, investing in deepening what already exists may be the wiser move.

In the first section, “Innovation Infrastructure,” Jakobovits writes of a visionary program implemented in a chareidi women’s school in Israel that enables inclusion on an unprecedented scale. The next two articles describe ambitious collaborations between day schools and university education schools: Stowe-Lindner on Bialik College in Melbourne and Harvard regarding the “Cultures of Thinking” project; Malkus and Sikorski on Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in Rockville, Maryland, and George Washington University regarding STEM and Jewish studies. Next, Cohen, the “Tech Rabbi,” gives advice for creating capacity for student innovation, and Mendelsohn Aviv discusses the creation of a new blended-learning school. Goodman and Frim present a Jewish multicultural school as a model that may appeal to millennial Jews. Articles by Kress and Truboff approach the challenge of making innovation stick from different perspectives, and English shows how some innovative day schools market themselves.

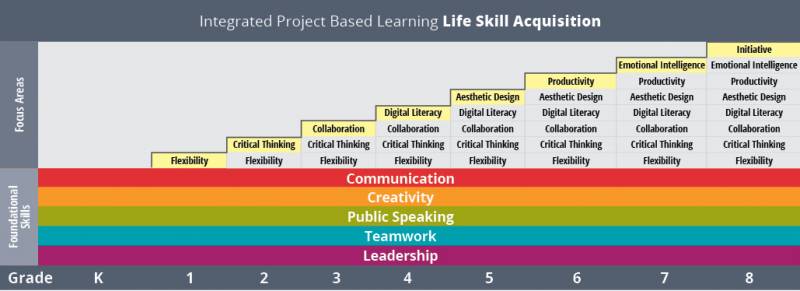

Our center spread features innovative ways that schools ignite student passion and inspire student ownership in tefillah. The next section looks at innovative initiatives within and beyond the classroom. The first two articles concern assessment. Soleimani explores how her school conducted a a curricular audit that gave direction for change and improvement, while Arcus-Goldberg charts the transition to student portfolios. Five articles then portray a variety of innovative educational programs. Marson takes principles of gifted learning into arts education; Jacobs and Spector detail the workings of I (Integrated) PBL; Nagel showcases her updated approach to modern Jewish literature; Reiss and Westman present a game-based app for biblical literacy; and Matas features a school that takes time off to solve real-world problems. In an excerpt from a recent book, Couros and Novak riff on cultivating creativity, and Freundel displays the creative energies and vision of day school leaders. Freundel's article represents the launch of a partnership between JEIC and Prizmah, including a series of articles on the Jewish Day School of the Future that will be featured in the months to come.

May this new year be one in which the innovative ambitions of school administrators and the innovative skills of teachers enrich and nourish the growth of our students’ capacities for innovative learning—while renewing the ancient wisdom of our tradition.

From the CEO: "What If?" The Jewish Tradition of Educational Innovation

Havruta,“two scholars sharpening one another” (Babylonian Talmud, Ta’anit 7a), is arguably the richest way to study Jewish texts. Yet until recently, it was a minority pedagogical style; it took change within the yeshiva education system to become the norm. According to Israeli historian Shaul Stampfer, havruta-style learning (pairs of study partners learning text together), although practiced since ancient times, became the predominant form of Jewish study only after World War I, when yeshivot opened their doors more widely. As described by Rachel Gelman Schultz, “Once yeshivot were no longer only for the elite, the students needed to learn in havruta in order to understand the difficult texts, and this mode of learning spread.”

Educational innovation is nothing new for Jewish education, whether related to sacred texts or general study. Innovation for Jewish day schools means applying new, or perhaps existing but under-used, ideas in search of continually delivering better learning for students. No matter a school’s educational philosophy or preferred pedagogy, all teachers want to improve and respond to the dynamic ways students learn.

At Prizmah, we see educational innovation as an important pillar of our work with the Jewish day school field. Our Strategic Plan calls for “fostering a culture of continuous educational growth and experimentation, and identifying and scaling promising new ideas.” On a daily basis, this is accomplished most readily through the myriad points of connection throughout the Prizmah Network. Whether in Reshet conversations, through a presentation at a Prizmah Gathering, in the informal learning at our summer pop-up learning hubs, or through the JDS Collaborative model, educators connect with each other to seek out and to share resources and knowledge.

This past summer, Prizmah co-hosted an Innovators’ Summit where educators and innovators from day schools and beyond were able to “show and tell” how technology and techniques such as Makerspace, Firestorm, CoSpaces and Virtual Reality are changing the way day school students learn. Innovation allows middle schools students in Indianapolis, for example, to collaborate with peers near Nahariya in a Virtual Worlds project and travel to Jewish communities around the globe. Participants learned about The Jeremiah VR Experience, a virtual reality application that takes students through the book of Jeremiah in an immersive experience, while also getting an overview of the current virtual reality market. Upcoming gatherings this year will include opportunities for the growing number of educational leaders in Jewish day schools to share and learn about both technological and other pedagogical opportunities to advance learning.

We know that a commitment to educational innovation pervades all levels of school leadership and is certainly not limited to, or even primarily centered on, educational technology. Our plan envisions a field where schools are able to enhance their educational visions and goals for academic achievement, social-emotional development and Jewish identity. We are committed to strengthening schools’ efforts to educate more students, by expanding their learning support, and by developing pedagogy to differentiate learning.

There may (mistakenly) appear to be a paradox in enlisting innovation to support and maintain connection to ancient traditions. Judaism itself, however, has always been inextricably linked to changing realities, as new questions arise and new answers are fashioned that build on the past. The opposite of tradition is not innovation but rather stagnation. When we adopt innovative approaches in our day schools, we integrate the best of new ideas with the values from our tradition. This can take many forms across many different types of schools: interdisciplinary approaches to Jewish history, for example, or child-centered study of Gemara. When we adopt a “what if” attitude, we usually see a result that exceeds even our wildest imagination.

Jewish day schools are unique in the landscape of the Jewish world as institutions where every day, new ideas blossom in the minds of young learners thanks to the careful and deliberate efforts of teachers who seed connections to tradition with the most innovative of techniques and approaches. Prizmah is encouraged by all that we see and honored to create settings where these ideas and practices are promulgated.

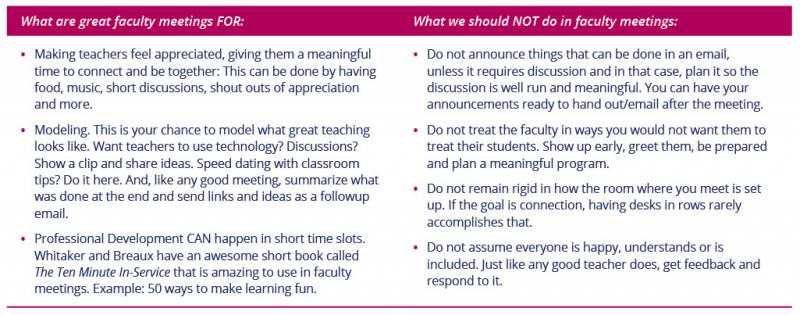

The Advice Booth: Faculty Meetings to Look Forward to

Dear Prizmah Coach,

I can deny it no longer: My staff hates faculty meetings.

What can I do?

Sincerely,

Well-Meaning Principal

Dear Well-Meaning Principal,

I hear you. We have all inherited systems that no longer serve us, but they remain ingrained in the school schedule, so we use them because:

- We are afraid that if we write an email, no one will read it. So we use meetings to announce things instead.

- If we stop having meetings, we will never be together, and it is important to at least see each other and build community.

- If we only have meetings “when needed,” then no one will come. Therefore, it is better to keep those we have on the schedule so people expect them and plan accordingly.

- Staff will be staff… they will complain no matter what we do, and there is nothing you can do to change that, so do not change the meetings.

- There is too little time to actually accomplish anything real, like professional development, during a short faculty meeting.

- And more…

Here is the truth—and I am going to tell it to you simply: YOU ARE WRONG. Yup. There it is, my friend. All of those reasons not to change—they are based on incorrect assumptions. But do not worry-we can help you. It’s time for a PARADIGM SHIFT.

Imagine, if you will, a faculty meeting where the team shows up, eager to get together. The administrators greet the team members at the door, welcoming them in by name. An agenda has been sent out in advance, and as teachers walk into the room, there is food, maybe music, and an atmosphere of welcome. What? You say this is too difficult? It takes too much time? Well, my dear principal, THIS meeting is YOUR lesson. This is your chance to model what you want to see in the classrooms. If you are late, unprepared, frontal, boring, and do not seem to have put in time to design a worthwhile program, then you are saying to your team that this is OK. Do not allow yourself those excuses. If you have a meeting planned, then make it count.

At Prizmah, our Educational Innovation team and coaches work with school leaders to rethink what effective, meaningful—and dare I say it—FUN faculty meetings might look like. We would love to hear about your success stories and challenges. Please be in touch at [email protected].

Commentary: Innovating in Depth

Something I have been focusing on quite a bit as of late is the idea of innovation in education being more focused on depth rather than being something new. For example, a lot of organizations (including education) are always touting being on the “cutting edge” as they are embracing the “latest and greatest” technologies or perhaps strategies. The problem with this focus is that if you are too focused on doing the “new” thing, you probably never had a chance to get good at the last item or initiative. It is a cycle that continues over and over again in too many spaces.

But if you stay focused on something too long, how can that truly be considered innovation? Think of it this way. The original iPhone was a marvel when it first came out over ten years ago, but if you have had any of the iterations since, you probably would not be excited about the limitations of the original today. Each iteration of the iPhone to the product we have today is an innovation. The more time we have to

focus on depth creates an environment where we can bring out the true artistry within teaching and learning.

George Couros,

“Innovation Focused on the Ability to Improvise”

Casey Suter, Elementary School Division Head, The Shlenker School, Houston

Educators are inundated with “innovation” on a daily basis. Companies contact schools with the latest and greatest new programs that guarantee outstanding student outcomes. Staying current with educational trends is important, but we know that just because a program promises excellent student outcomes does not mean it delivers on that promise.

Our school seeks out research-based programs and curricula for our campus. Each year, we develop a needs assessment to ensure that we are providing teachers with proper teaching methodologies to strengthen current programs. Our teachers are required to attend 25 hours of secular and eight hours of Jewish studies professional development each year. Our focus is to provide teachers with professional development that deepens their understanding of current curriculum. We have learned from experience that great teaching comes from teachers with deep understanding of curriculum, knowledge of targeted planning and strong delivery of instruction. Educators, not programs, change student outcomes.

Bracha Rutner, Assistant Principal, Yeshiva University High School for Girls, Holliswood, New York

In education, we have often rushed to embrace new technologies such as smartboards or 1:1 computers once they became affordable, mostly through grants. We have found them to be useful, sometimes, in a specific context. But they remind us that the real way students learn is when they feel safe and comfortable with a person with whom they have a relationship.

I often wonder if educational innovations are really so different than what we did in the past. How did teachers often begin their class? Many midrashim employ a petichtah, a story or idea with which a rabbi would begin a class with to entice the student. Today, we call that a “do now.” Students needed to know Tanakh well before studying Talmud—i. e., “scaffolding.” And then the rabbi would delve deep into the learning, using examples to initiate questions—a variety of “inquiry-based learning.” And how do we know that we needed to personalize learning? çðåê ìðòø òì ôé ãøëå. Today, we know that students learn better in small groups as opposed to constant frontal teaching; earlier, we called this chevrutah. The Tannaim and Amoraim were not afraid to embrace difficult issues and neither should we in education.

If we look at new ideas through the prism of the past, we may find that they are not as much of a fad as they seem. And it is helpful to address new ideas if we use them to build on the sound foundations that we have created.

Rabbi Jonathan Berger, Associate Head of School, Gross Schechter Day School, Pepper Pike, Ohio

The world of education often oscillates between two poles: innovation and tradition. The unstated message is that we must choose between being progressive educators, constantly changing, or “old school,” proudly and cautiously reliant on the tried-and-true. Embracing progressivism means that we can’t stand still; being traditional entails a stance of suspicion towards anything new. And of late, educators’ understanding of innovation has been shaped by Silicon Valley’s model of “Move fast and break things.”

George Couros’ alternative to this model accords well with Jewish practice. On Simhat Torah, we finish reading the Torah and start it again the very same day; when we celebrate finishing a tractate of Talmud, we declare that we plan to return to it. In both cases, the goal is to discover new interpretations and perspectives when we reread. Our practices mirror Couros’ idea of seeking new insights and greater depth, not just moving on to something new.

But this model of innovation can lead to complacency. Sometimes, small, iterated improvements aren’t enough, and more radical changes are needed. How do we know when to innovate radically, and when to aim for depth and true artistry? A good supervisor or coach helps us to constantly reflect and improve, and a strong school accreditation process ensures that every few years, every aspect of a school is evaluated. Together, supervision and accreditation can help us find a dynamic balance between steady small-scale innovation and occasional radical change.

Research Corner: Assessing Our Workplaces

One of the most frequently asked questions we hear from heads of school is, How can I find and retain top talent in my school? In order to support our schools in ensuring they are great places to work and to create conditions to attract top talent to the field, Prizmah partnered with Leading Edge, the Alliance for Excellence in Jewish Leadership, to offer their Employee Experience Survey to day schools. This initiative was offered at no cost to schools through the support of generous federations and foundations.

In May, 22 schools administered this survey, and more than 1,400 staff and faculty participated. The survey focuses on employee engagement: the level of connection, pride, motivation and commitment a person feels for their work and how likely they are to stay or leave their place of employment. At Prizmah, we want to ensure our schools are incredible places to work. At the heart of our work is the people, and this tool supports schools in their efforts to identify ways to ensure the people who have chosen to devote themselves to the enterprise of day schools feel wholly engaged and supported in their work.

Among the key survey findings:

Jewish day schools excel at ensuring employees feel strongly connected to the mission of the school. Employees express a good understanding of the school’s mission, they deeply understand how their work contributes to the organization’s mission, strategy and goals, and they state that the mission of their organization makes them feel like they are making a difference in their work.

Employees feel comfortable asking for help from one another when needed, and they seek opportunities to collaborate with peers. The highest rates of favorable scores reside within teams where people feel most connected to the work and to their colleagues.

Faculty and staff value flexibility and autonomy within the school and appreciate the opportunity afforded by their positions to do challenging and interesting work.

Direct managers have great leverage in creating conditions within their teams where employees feel supported, well-cared for, and clear about priorities and responsibilities.

The data reveals areas where improvements would advance employee engagement:

Strengthening internal communications. Employees give higher scores for communications with direct managers and within departments than within the organization overall.

Managing performance through appropriate and ongoing feedback. Fewer than half of respondents said they receive regular feedback on how they are performing.

Ensuring a more even distribution of work across portfolios. While employees felt they have the information and resources to do their job well, fewer feel there are enough people to do the work.

Setting and communicating an organizational compensation philosophy. Few employees understood how salary decisions and raises happened at their organization and how salary scales compared to similar positions in other schools.

All of the organizations that participated in the Leading Edge survey were offered a one-on-one consultation with a Prizmah consultant to identify an approach to address the opportunities and challenges they face in their school and develop plans for next steps. Prizmah offers support to schools in facilitating leadership-team retreats, workshops on school culture, and coaching for senior leadership and boards.

Often, so much in a school feels both urgent and important. This tool is an effective way to identify what levers to pull on to maximize impact, create a safe space for employees to reflect on their experience within their organization, and give shared language to schools as they chart a path forward. We look forward to measuring progress over time and to supporting our schools in developing strategies and prioritizing work to ensure we create conditions where leaders can thrive.

On My Nightstand: Brief reviews of books that Prizmah staff are reading

The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business

By Patrick Lencioni

If you could do one thing this year that would dramatically improve your school, what would it be? Lencioni asserts that focusing on organizational health is the key. Lencioni, well known for his clear and simple style of writing, untangles the complexities of leadership and offers concrete ideas and practical steps to shift the way we work as he tackles our fundamental assumptions about what matters most.

Perhaps most challenging is Lencioni’s belief that the tools and resources needed to shift to becoming a healthy organization lie within the staff of the organization itself. What might we shift in our practice if we believed it were within our reach to make changes that could fundamentally shift our schools? What if our avoidance of uncomfortable conversations, our desire to solely immerse ourselves in data and strategic planning, prevents us from dealing with what matters most? While culture can be challenging to measure, the absence of a healthy culture can make all the difference in why some companies succeed and others fail.

This is essential reading for any school lay or professional leader and for our Jewish communities as a whole.

Ilisa Cappell

Storytelling with Data

By Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic

Bad, incoherent, hard-to-read graphs are everywhere. Most people aren’t trained statisticians or skilled at telling stories with the data they have. Anyone who creates graphs to report on data could learn something from this book. Nussbaumer Knaflic provides step-by-step insight into great data visualization practices that will enhance your visualization, enliven the story of the data and improve the message you are trying to convey.

The book gives clear advice on how to create effective visuals by showing examples of typical graphs that we encounter and then unpacking how they could improve. Here are the three major takeaways: think about what you want your audience to know and do with the data before designing the graph; minimize clutter—less is more with graphs; focus your audience’s attention by using color intentionally.

Odelia Epstein

The Jewish Cookbook

By Leah Koenig

I savor the community we build in the kitchen and around the table. My cookbook shelf, and my cooking repertoire, is filled with Jewish food. Gil Marks, Joan Nathan and Yotam Ottolenghi grace my shelf and have been my rebbes in the kitchen; do I really need another Jewish cookbook? With this book, the answer is a resounding yes.

Koenig reminds us that Jewish cuisine is more than just matzah balls and potato kugel. I’m particularly excited to try the dozens of recipes that will push my culinary boundaries beyond my own Ashkenazi heritage, and those that show that Jewish food has been shaped by the cultures and flavors of our millennia of Diaspora: Persian jeweled rice, sweet potato-pecan kugel inspired by the flavors of the American South, and especially gulab jamun—rosewater fritters from India’s Bene Israel community.

Koenig’s extensively researched and meticulously tested recipes will ensure your success, whether you’re trying something new or looking to recreate a classic. And the beautiful photography and thoughtful design invite in both the experienced cook and the kitchen dabbler. I’m looking forward to a table graced by these wonderful recipes for years to come.

Daniel Infeld

Somebody Else’s Children: The Courts, the Kids, and the Struggle to Save America’s Troubled Families

By Jill Wolfson and John Hubner

This nonfiction thriller written by two journalists, one a former probation officer, walks you through the lives of children, teens, young adults, new parents and families impacted by the child welfare system, from court hearings to custody placement. The book expounds upon individuals’ experiences, while also highlighting the negativity, confusion and fascination that is typical of American family courts. Some of the people have lived a lifetime in the system, experiencing a gamut of shelters, courts and foster homes and a roller coaster of frustration, sadness, betrayal and sometimes reunification. However, for others, the system has served as a stepping stone for opportunity and change.

The world described in this book may seem far from the experiences of most people in our schools and communities, although it is a common feature for many in our society. Too often, we take for granted the resources provided to ensure perpetuation of education, love and support. While this book can be heavy at times, its description of the many people working to support these children reinforced my sense of commitment to our community and country.

Sara Loffman

Educational Innovation in Special Education: Turning It Around

Visionary programs of inclusion can be found in all kinds of Jewish schools. HaYidion asked the developer of one such program at the Beth Jacob Institute of Jerusalem, among the “Ivy League” schools of the chareidi world, to contribute this description of their pioneering work in the field.

The striving for integration of mentally, emotionally and physically challenged individuals into society is one of the noblest innovations of the modern world. Many programs have been developed in an ongoing search for the most appropriate and effective ways to do this successfully. Most of the work involves integration in the classroom and the workplace; significantly less research and experimentation has been done on the inclusion of people with disabilities into society as a whole. An exception to this is the work of the Beth Jacob Institute of Jerusalem (Machon Beit Yaakov Yerushalayim), a girls’ high school and advanced education school, with more than 3,000 students. Of these, 280 compose a special education department, serving a very broad range of special-needs students, aged 14 to 20 and older.

Thirty years of experience with a variety of methods at the Beth Jacob Institute have honed the sense that current methods—which generally define the aim as “acceptance of the other,” “removing the stigma,” and “helping the disadvantaged”—are qualitatively insufficient. They perpetuate in the special-needs individual an inferior status, which can and should be eliminated. Beth Jacob has developed a groundbreaking program which has as its goal the equal-status, genuine inclusion of people with special needs into society, to the benefit of both.

The Beth Jacob Institute of Jerusalem constitutes a microcosm of religious society in Israel. Because of its educational emphasis on acts of kindness and good deeds, it provides an excellent environment for testing ideas about social integration of the specially challenged. The Special Education Department was renamed as the Telem Center of the Beth Jacob Institute of Jerusalem, using a Hebrew acronym for “Individually Adapted Programs.” Many transformations accompanied the name change. In the past, integration programs at the Institute included part-time, individually suited inclusion of special-needs students in the formal academic classes of the mainstream school, technical training classes, informal school activities, pairing of students in tutorial relationships, etc. These programs were in line with the most advanced studies in the literature, but there was still considerable frustration, resulting from the obvious gaps between the abilities and skills of the general and special student populations. Invariably, there lingered a sense that mainstream students were being asked to assist the special needs students as an act of kindness. To the degree that the interaction between able and disabled students was achieved, it was strictly limited to the times of the integration activities and did not carry over to relationships beyond the prescribed frameworks. Barriers were penetrated but not removed.

Driven by the conviction that further progress could be made toward genuine inclusion into normative society, the Telem Center concluded that what was required was a new and more sophisticated methodology. To make the leap to a strategy that could take participants beyond the impediments and limitations of previous interactions, three prerequisites were emphasized:

- Factoring in the needs of both mainstream and special needs students

- Expanding the interaction to areas well beyond academics

- Addressing authentic needs of all participating students

Abraham Maslow’s well-known hierarchy of human needs was used as a starting basis for constructing a program for participating students. But Maslow based his analysis of human development on studies of the most able and accomplished human beings. The hypothesis on which the Beth Jacob Institute’s new work was based was that, when applied to the points of excellence which are present also in disabled individuals, the same ladder of needs can be climbed by all, leading to satisfaction, recognition and equal-status interaction.

The Yad leYad Theoretical Model

Extrapolating from Maslow’s hierarchy, a theoretical model, called Yad leYad (Hand to Hand), was developed by the Telem Center to direct an equal-status inclusion program, named Yedidut (Friendship). The Yad leYad model is composed of ascending, interacting levels.

Level 1 – Hierarchy base: Formal and informal studies, language development, capability-building and empowerment, including “mainstreaming” experience at the school, as a basis for future inclusion in the community.

Level 2 – Physiological needs: Organized and well-structured basic conditions. A network of workshops planned and directed by a professional team that directs all the activities at the school.

Level 3 – Safety: Mutual goals with normative students, creating a safe space for participants with special needs to join in normal activity. The organized network of workshops with professional guidance supplies the security needed for functioning properly.

Level 4 – Belonging: A joint product in exhibitions and performances fostering group cohesiveness and communal belonging that transcend the boundaries of the proposed program, revealing the strengths of the student with disabilities, and enabling the mentors to understand their differences and see the whole person. This understanding sets the stage for a relationship to form, and fosters openness and communal involvement.

Level 5 – Esteem: Providing positive feedback to the participants as to their areas of strength, boosting their efforts to keep up the relationship and enhancing their ability to give, love, demonstrate patience and empathy, and more.

Level 6 – Self-actualization: Through the sense of capability born of the relationship and the connection to the program’s community, fostering an inner emotional gratification, a connection to one’s own personal abilities and personal empowerment, and fortifying the participants’ desire and ability to develop more social relationships.

The Yedidut Program

The Yedidut program is a real-life embodiment of the Yad leYad model, enabling participants to build genuine mutual friendships that are meaningful and lasting. It has effectively broken down barriers between the two student populations at the Beth Jacob Institute.

The program begins by pairing mainstream students and students with special needs for activities outside the classroom in which they have a common interest. To this end, Yedidut offers a large number of weekly workshops in activities such as acting, dancing, painting, choir singing, clothing design, acrobatics, fruit arrangement, cooking and drama. Each pair of friends-to-be chooses the workshop of their liking together. Thus, from the outset, Yedidut identifies and brings into focus points of excellence in all participants, points that can be cultivated and that jump-start meaningful relationships.

At a later stage, group events are held to bring the participants together. These activities are accompanied, guided and carefully calibrated by skilled, experienced and motivated staff. From these beginnings, friendships expand exponentially to voluntary, self-motivated, all-week-long interaction, both in and out of school, and to wider and wider circles of friendships, thus effectively infusing the future lives of the participants, their families and communities, with the compelling energies generated by their inclusion experiences during their school years.

Here is the sequence of stages that the Yedidut program follows:

Stage I: Common interest. A “mentor” and a “mentee” register jointly for a workshop of their choice in an area of common strength and interest.

Stage II: Common goals. Developed in the course of the workshops, a common goal creates reciprocity and interdependence for the achievement of the goal, under the guidance of the professional team.

Stage III: Joint action. The students bond over activities in the various workshops—not based on language or academic studies. Dance, drama and cooking help the girls learn socialization techniques and discover solidarity and close social contact.

Stage IV: A product. Throughout the duration of the workshop, students work in unison to produce a performance, an exhibition, etc. Joint products allow the students to experience success and help expand the communication circles on both sides.

Stage V: Communication circles (in the chosen field of interest). The students’ joint activity in areas of mutual strength and interest, the pleasure derived from the workshop, and the social empowerment fostered at each stage of the program all merge to form a relationship that expresses itself also outside the actual framework of the workshop.

Stage VI: Broad natural-communication circles. In this stage, some of the partnerships expand to develop communication circles outside the specific area of interest represented by the workshop. These communication circles may include activities such as mutual home visits and shopping together, with the goal of deriving another positive experience from the friendly relationship. This is the deepest and most significant stage of the integration. Moreover, this friendship brings with it a network of friendships and acquaintances that encompasses the students and further integrates them into normative society.

The effects of the Yedidut program have been extraordinary. A new world of joy, achievement and personal growth opened up to all participants. The mother of one student with special needs noted that inclusion programs had not worked for her daughter because “putting them in a regular classroom means putting them in a place where their differences are very pronounced. Instead of highlighting similarities, this highlights differences.” The Yedidut program altered this dynamic completely.

Mainstream students and students with special needs alike have been energized and newly empowered. They discovered that everyone has something to contribute, that their friendships are truly friendships and mutually enriching and that everyone is, indeed, an equal-status member of a many-faceted society. One participant observed, “I was taken by the fact that when the girls focused on their strong points, their weaker points seemed to fade into the background. And this helped me to relate to my own weak points. I discovered my own weak points, and I learned to deal with them and see them.” Another commented, “This is actually what happened to the girls in the regular classes. They said, ‘Just a minute. It’s true that she talks slowly, it’s true that she thinks slowly, it’s true that she looks different. But as soon as she picks up that knife and starts cutting the cakes and creating those petit fours, she’s amazing at what she does. So she’s not just disabled.’ They began to relate to the bigger picture, to see the whole person. They realized that these girls can be much better than them at other things.”

Parents have been happy to find that formerly introverted, insecure and non-communicative daughters, including those on the autism spectrum, suddenly developed greater self-confidence. One student explained, “My communication with people simply changed. It has become so much smoother. The moment I realized that people enjoy being with me, as I am—the way the girls accepted me as I am—it gave me something that extended beyond. It impacted my more extended environment as well.”

Perhaps the most significant success of the program was the diminution of differentiation outside of the classroom. One mother described, “It created a brand-new possibility for her: ‘Yes, I can! I can be together with them.’ Because it’s not in a framework of studies. It’s in a fun, enjoyable framework. And even in the workshops where she actually does something, they do it with her. It’s the pinnacle of social interaction.” A participant elaborated, “In the past, I never saw these girls going out to the yard during recess. Never. Since this started, they go out—ecstatic! When they’re there they feel like they’re really part of things. They’re really together with everyone else. And for our part, as well—you know, everyone asks me, ‘Wow, you have other friends?’ I feel like they are my friends just like any other regular friend.”

In the three years since its inception, the reverberations of the Yedidut project have touched and significantly improved many lives. As one mother explained, “I have a cousin here, somewhere in this massive school, in a regular class. Every time I meet her, I say, ‘You have no idea how great it is for Racheli that you’re here.’ She tells me, ‘Racheli doesn’t even need me. Racheli has tons of friends here, everyone, all the girls in the hallways.’ But in her former school, Racheli was the kind of girl who was always on the sidelines. She wouldn’t talk. We didn’t hear from her. No self-confidence. Before she came here, she was like a little invisible dot in the corner of the room. Now she’s a flower.” Another mother added, “She says, ‘When I go into a room, they notice me. I walk down the hallway and someone says hello to me.’ This sense of belonging, we know what a basic and fundamental need it is.”

The innovative Yad leYad theory of equal status inclusion deserves to be widely adopted in the Jewish educational world and beyond. The trailblazing Yedidut project can serve as a model for others to emulate.

A Learning Ethos That Fosters Deep Thinking

Melbourne, Australia, is a long way from anywhere. Our nearest Western neighbor, New Zealand aside, is a 14-hour flight away. Consequently, a determined internationalist outlook, an investment in development, and a focus on excellence through teaching and learning are musts in order to provide a gold standard of education that persuades our community to buy into the Jewish schooling model.

Jewish schools are leaders in values education. They have clear mission statements that articulate an ethos to parents, be it denominational or pluralistic. They have the staff and the structures to embed these values in both curricular and co-curricular experiences.

But how many schools are able to be as clear in their articulation of their learning ethos? In good schools, teachers know what to expect, and what is expected, from a Jewish perspective. Most schools have structures in place—reporting, assessment, technology platforms—to support lesson planning and delivery. But how is the student experience different in different math classes? How different are the experiences in different elementary teachers’ classrooms within that same school?

Just as teachers should not be automatons, so should schools. Individual flair and nuance are parts of what makes learning interesting and differentiated. We expect teachers to be individuals, and supporting the development of a teacher’s unique craft is essential for their effectiveness as pedagogues. Likewise, a school’s unique and individual pedagogy should not only be supported, but should be as transparent and known as its Jewish values.

In 2005, Melbourne’s Bialik College, together with Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, began the Cultures of Thinking project, funded by Bialik parents Abe and Vera Dorevitch. Bialik became a research site, and the resultant book, Making Thinking Visible (co-authored by Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church and Karin Morrison), helped to popularize routines to nurture deep thinking throughout the global educational landscape.

Bialik’s determination is to make pedagogy as clearly articulated for student, teacher and parents as its Jewish philosophy. On the walls, documentation plots the learning journey of individual children. Rarely is “finished work” on display: The process of learning is what is showcased. Do we care about the finished product? Partially. But we are a school and not a museum. The struggles that we face in our learning are much more powerful and impactful than the glossy ending.

The articulation of a clear learning philosophy was evident throughout the early years of the school. As Australia’s first Reggio Emilia-inspired building, the Early Learning Centre for children aged 3 months to 6 years breathes pedagogy; the school even sent the architect to Reggio Emilia in Italy before designing the first building more than 20 years ago. When the primary (elementary) school was refurbished, for example, children made the cases for the mezuzot. By each mezuzah is a panel where the child explains their learning journey in the creation of this art.

The Culture of Thinking in the whole school is a natural partner to the Reggio Emilia-inspired approach in early learning. Cultural forces are a cornerstone of the approach. They are the tools and levers that educators use to shape classroom and learning. An awareness of the cultural forces in both curriculum planning and lesson planning ensures that there are clear expectations (a cultural force) for learning, that the environment (another cultural force) is used throughout the learning process, and that the language needs for the wide variety of students is incorporated into both planning and lesson delivery.

Thinking routines, of which there are dozens, provide opportunities to constantly delve deeper, assess and analyse critically, and expand upon learning. Rather than simply reflecting on a piece of work, we may use a CSI (Color Symbol Image) routine. Analyzing changes in thinking and perceptions may be channeled through a I Used To Think, Now I Think routine, while summarising key points may be achieved through a Headlines routine.

Deep thinking is embedded in the child through the school’s pedagogy.

Every new teacher at Bialik receives the Making Thinking Visible book before they commence employment. Through ongoing professional development, twilight seminars (after-school learning for educators from Bialik and other schools, delivered by our own expert educators and our consultants), day seminars, a biennial conference for 400 educators from around the world and research groups, teachers hone their craft in line with the pedagogy of the school.

Bialik has contracted with different researchers from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in order to develop and extend our Culture of Thinking within our classrooms. This is a significant financial investment on the part of our school community, especially given our geographical distance to Boston, USA. Our current researcher is Edward Clapp, who is working with teachers in grades 5 to 9 to develop a distinctive middle school pedagogy under the umbrella of Cultures of Thinking focusing on “participatory creativity” (the title of one of his books). To build our conceptual framework, Clapp has motivated the team to inquire deeply into their practice through his consultancy over the past two years. He travels to Bialik from Harvard twice per year, visiting classes, conducting interviews with teachers and documenting learning. In addition, he has conducted Skype discussions each month based on professional reading of his textbook and mentoring each teacher in the next stage of their pedagogical journeys.

Through this collaboration, teachers develop their own research projects to further their practice in collaboration with the school’s pedagogy. From this experience, teachers have developed an iterative exhibition to showcase a snapshot of their research. Here are some examples.

In grades 3 and 5, an investigation into Aboriginal art installation both at Bialik College and in our city’s national gallery has unearthed misconceptions and prompted discussions about appropriation of Aboriginal culture by the white majority. Our children have been questioning how we invite others into the creative process and who actually owns the creative process: Is Aboroginal art, for example, a purely Aboriginal process and experience? What is the role of the white commissioner, purchaser or viewer of the art?

A math teacher has linked the research into a wider project we are involved in concerning anxiety in the mathematics classroom. Math students have become documentary makers, and the films are being used for collective reflection on the learning process.

Another project is addressing students’ perceptions of failure. The class is investigating the importance of failure as a learning tool. A set of supportive questions have been designed to help students capture the heart of their response to moments of failure.

Grade 9 Jewish studies students are using primary source materials and texts to refocus attention on ideas, rather than grades. Grade 10 Israel and media students have been focusing on the biography of an idea. In analyzing ideas such as statehood, patrilineality, independence, what are the Jewish and secular sources behind these concepts? Who are the early thinkers, and how have those thoughts evolved over time? Have they been manipulated or misappropriated, and are such evolutions appropriate?

Pedagogical development and ideology are not established by chance. The board’s devotion to professional learning is backed by financial resources. This enables us to employ a dedicated senior leader overseeing pedagogy; to bring top educators from overseas to Bialik, and to send six Bialik staff overseas every year, to Harvard, to Reggio Emilia and to Israel, with an explicit commitment for these staff to lead professional development for colleagues on their return. Bialik’s clear pedagogical direction, with a focus on consistently spectacular academic outcomes for an academically diverse cohort, coupled with its clear Jewish mission, reaps rewards.

How a University and Jewish Day School Can Collaborate on Curricular Innovation

Can a Jewish day school partner with a world-class research university to accelerate student learning and drive innovation? What does it look like when university faculty teach elementary school faculty on a day school campus? How might a Jewish day school develop a unique and cutting-edge approach to teaching Judaic studies?

The Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School (CESJDS) and the George Washington (GW) University Graduate School of Education and Human Development explored these questions when we created and implemented an integrated STEM and Judaic studies Lower School (JK-5) curriculum, using the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Crosscutting Concepts as an organizing principle. The crosscutting concepts are a way that NGSS link different domains of science; they describe patterns such as cause and effect, scale, proportion and quantity, systems and system models, energy and matter, structure and function, and stability and change. In our project, teachers and students used the crosscutting concepts to organize learning across general studies (math, science, English language arts, social studies), specials (art, music), and Judaic studies (Hebrew, Israel, and Jewish texts and customs).

Our project started four years ago with CESJDS’s strategic plan goals to develop partnerships with local and national organizations, and to enhance STEM, science, and math instruction. The school had been progressing in STEM education and wanted to make a qualitative leap to be a best-in-class STEM learning institution. With a philosophical emphasis on integrated curriculum at the school, we saw an opportunity to advance not only STEM but to innovate in Judaic studies.

After an RFP process, CESJDS entered into a partnership agreement with GW. GW brought expertise in STEM and teacher training to the collaboration, and CESJDS brought knowledge of Judaic studies, an innovative mindset and experience in integrating Jewish and general studies. The product of our collaboration was a three-year professional development program and a fully articulated integrated curriculum. Each unit in the curriculum used a crosscutting concept as the central theme, which served as the basis for integration of different subjects.

PARTNERSHIP STRUCTURE

The project was led by the STEM coordinator at the CESJDS Lower School and a GW faculty member. To start, CESJDS administrators invited teachers from different grade levels and content areas to take a leadership role in the curriculum development project. These teachers met weekly for one to two hours with the GW team. Teachers were relieved from some responsibilities in order to participate in these weekly meetings. The GW team included math and science education faculty and a doctoral student with prior elementary teaching experience. After three years of coursework and participation in the project cohort, CESJDS teachers received Graduate STEM Educator Certificates, allowing the school to build teacher expertise and capacity. The project counted toward GW faculty’s research and teaching responsibilities, and provided the doctoral student valuable first-hand experience in teacher education and education research. Together, the CESJDS and GW team organized our efforts on three types of activities: curriculum development, teacher professional development, and research and evaluation.

CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

One of the primary objectives of the partnership was to develop a set of integrated curriculum units (called “Kaleidoscope Projects” or KPs) for grades 1-5. The integration effort was informed by prior research into what supports and what hinders teacher collaboration in pluralistic Jewish day schools. Early on in the project, CESJDS teachers and the GW team studied Robin Fogarty’s article “Ten Ways to Integrate Curriculum” together.

The Kaleidoscope Projects were designed by the classroom teachers and documented by the university research team. KPs were created, piloted and then refined, with the integrated nature of the units deepening each year. Each grade level set a target of developing two to three KPs per year. We created a standard KP format for consistency across grades. All KPs included a STEM subject, and most contained a Judaic studies and/or a Hebrew component and a languages arts subject. Through this type of integration, the school was able to teach Judaic content in a relevant way for students and to make real-world connections between Judaic studies and other subjects.

TEACHER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The curriculum writing was based on a core belief that to truly innovate in STEM and Judaic studies, we needed to invest in building teacher capacity. The curriculum-making project required a core team of teachers who would take leadership for their grade-level teams and/or content areas. Teachers in the core team—approximately one per grade level, together with subject specialists—completed a 12-credit graduate certificate through GW.

In meetings, teachers learned about the crosscutting concepts and brainstormed KP ideas. For example, at one meeting, we looked at the existing second grade curriculum to find natural connections to the concept structure and function that could be the beginnings of a KP. The general studies teachers pointed out that all second graders learn to write various types of poetry and study the relationship between a poem’s structure and its function. Judaics teachers made a connection to character education (middot tovot of the CESJDS curriculum) and how the structure of a space can facilitate citizenship and participation. Teacher meetings were an opportunity for sharing lesson plans and materials and studying student work created in the KPs. While the teachers had assigned reading on STEM, integration and the crosscutting concepts, most of the “homework” for the program was the writing and piloting of the integrated units.

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION

The original project plan called for both evaluation of the units and research activities. Our evaluation focused on assessing the effectiveness of the curriculum and the project in meeting its goals and providing data that would guide the work beyond the initial three-year period. The research was aimed at extending the knowledge base on how to support elementary students’ science, math, Judaic studies and language arts learning in an integrated curriculum.

The core teacher group was called the Curriculum Integration Leadership Team (CILT). They made significant advances in understanding crosscutting concepts, curricular integration and assessment, as documented in the professional development meeting minutes and teachers’ planning materials. In terms of documenting student learning, the research and evaluation components of the project underwent significant redesign each year due to low parent permission rates. We encountered challenges obtaining consent; recent national and international events that have heightened societal awareness of security and privacy were contributing factors.

PROJECT OUTCOMES AND IMPACTS

The first year of the project focused primarily on professional development and curriculum development. We established the CILT, ran the first teacher courses taught by GW graduate school faculty, and created the first two Kaleidoscope Projects: Robot Shabbat and Rube Goldberg™ Machines.

During year two, the CILT studied the crosscutting concepts and different models of curriculum integration. We also examined opportunities for stronger arts integration in the KPs. GW and the third grade teachers worked together on projects called Ecological Communities and Where Does All the Water Go? Other grade levels created multiple crosscutting lesson plans for expansion into full projects. The CILT presented some of their lesson planning work at regional practitioner conferences.

Finally, in the third year, curriculum development ramped up to meet the goal of developing 10 to15 total KPs. The professional development concluded with teachers completing the final STEM Master Teacher certificate course focused on engineering integration. The project team gave multiple presentations of their work at local conferences. The GW team submitted a manuscript to a leading peer-reviewed science education journal. Last, the CILT met multiple times in the spring and summer to determine what elements of the project should continue moving forward, and what supports would be needed to sustain those elements within the school.

Professional development was a central component of the project. Rather than design curriculum and train teachers how to use it, this project focused on teachers as curriculum makers. The professional development was designed to help teachers take their ideas for units and turn those into high-quality curriculum. The professional development served another important function: It established the teachers as leaders who could support the rest of the faculty in future curriculum development efforts. Overall, GW provided 120 hours of professional development time. Though the credit-bearing option was limited to a small group of teachers (10 initially), the weekly meetings were open to all teachers throughout the school. The CILT’s potential as a source of expertise and support for schoolwide curriculum integration is a lasting impact of this project.

During the third year, we conducted a survey of all grade-level teams to gauge teachers’ knowledge of, comfort with and commitment to using crosscutting concepts as the central organizing principle for integration. The entire faculty was aware of the project and involved in different ways throughout the three years. The survey indicated that teachers were very comfortable with the crosscutting concept assigned to their own grade team, but needed more support to understand the crosscutting concepts in other grades. Teachers felt that students developed a better understanding of crosscutting concepts but wanted more evidence that the integrated nature of the project supported student learning in the various content areas. Since the GW-CESJDS STEM Integration Project is one of the first documented efforts to utilize crosscutting concepts in a systematic way across elementary grades in the United States, it has served as a pilot school for this national initiative.

We also surveyed the CILT teachers about their experience in the project. We learned that CILT teachers’ understanding of integration, crosscutting concepts, and assessment deepened dramatically over the three years of the project. For example, in the early years of the project, teachers’ assessments of student learning focused on vocabulary use and/or tagging phenomena with a crosscutting concept (“What’s an example of structure and function?” “Where do you see cause and effect?”). By the third year, teachers were trying to assess what students can actually do with crosscutting concepts, and how their knowledge of the concepts impacted their learning of new content in the various subject areas (“How can the crosscutting concept stability and change help third graders understand choices that characters must make in Parashat Lekh-Lekha?” “How does the patterns crosscutting concept help first graders remember and understand the different aspects of Shabbat?”). We suggest that many of the positive outcomes can be traced to the integrated nature of the curriculum and the teachers-as-curriculum-makers design of the project.

Overall, the opportunity for a research university and a JK-12 pluralistic Jewish day school to partner together on curriculum development and professional development had a major impact on both institutions and on the day school students. We have developed a cadre of highly skilled master STEM educators in a Jewish environment, developed a unique, integrated curriculum based around crosscutting concepts, transformed how teachers think about integrated instruction, and modeled how graduate faculty can teach and learn at the elementary level. We are working to disseminate the curriculum and research findings to the larger field so other schools can consider adapting this model.

Designing the Space to Cultivate Creative Capacity

Before surveying educators about whether or not they view themselves as creative, I challenge them to define the word “creativity.” Most define the term as meaning being artistic, musical or gifted in some other act of making something. While these are without question forms of creative expression, they do not define or even represent the essence of what creativity is and by extension could be. This narrow scope associated with creativity pushes many young people away from trying to figure out what creativity is for them and how they can impact the world around them.

So what is creativity? I define it as a mindset. This mindset uses various methods to observe the world, identify problems or challenges, and ideate a solution that, if successful, will bring value to others. Picasso did this through art and Mozart through music, but it also can be accomplished through organizing an event or developing a plan to support learners at varying levels of mastery. Creative capacity can be built without lifting a paintbrush or playing a note. From this realization, we can begin to develop our creativity and help instill the confidence needed for our students to do the same.

Creativity is often associated with thinking “outside the box,” striving to help students engage in nontraditional methods of learning while maintaining the same academic standards as “in the box.” One of my favorite students was just not an in-the-box kid: He built six boxes in the box and made sure his box was safe and secure from any attempts at the unscripted and unknown. He was one of the inspirations that pushed me to publish a book on cultivating creative capacity titled Educated by Design.

I needed to document the principles I hold to when standing up to a challenge and taking it head-on. The principles are organic and stand on their own, and while there are other equally important critical components to building creative capacity, these 10 build on one another and provide everyone the opportunity to reveal their innate creative potential.

1. Creativity is a mindset, not a talent. Remember it starts with a mindset, but the purpose of creativity is to move beyond ideas and turn them into something actionable.

2. Failure is a stop on the journey, not a destination. No one likes failure; those who say otherwise either aren’t trying anything significant, or are so scared of failure that the only way they cope with it is to pretend to love it. Nevertheless, by creating experiences for students where they can fail, grow and build resilience, we give our students, and by extension ourselves, the best chance at bolstering creative problem-solving abilities. Learning should be designed not as a one-time, summative experience but rather as a scaffold of multiple iterations that allow students to reflect and refine their work.

3. Empathy inspires creativity. True creativity is about bringing value to others. How is that value developed? How well does the artist or musician know their audience? How well does their product address the whole person? Teaching empathy is a critical skill for students to be effective problem solvers, communicators and leaders. When you ask someone to define empathy, many times they start defining sympathy instead. Empathy is defined as the ability to understand the unique needs, challenges and realities for someone so you can best support and engage with them on their terms.

4. Collaboration is a prerequisite for innovation. In school, students need to engage in cooperative experiences where they are all accountable for the same scope of work and need to work together to make sure the project is complete. Collaboration isn’t about just working together; it’s about leveraging each group member’s strengths, skills and knowledge to arrive at a more significant outcome. Students need to learn to establish project roles that provide equal value to the project not just in quantity but quality. A great example is having students create video content. There is directing, scriptwriting, filming, editing and post-production. Each phase is vital to the success, but the director rarely sits down and starts editing the footage. When building a technological prototype, you have roles in planning, design, construction, programming and troubleshooting. Once again, each role is critical, and the defined roles result in a richer learning experience and outcome.

5. Ideas should lead to action. Ideas inspire us but they aren’t usable. A big challenge in the world is how to take an idea and develop it into a solution that can be used by others to improve their lives. Schools should empower students to take content knowledge, come up with an idea to solve a problem and then act on it. By challenging students to tackle real-world problems, they can leverage the knowledge and skills gained in the classroom as they brainstorm solutions to problems around them.

6. Technology is just a tool. Technology is part of nearly every facet of our lives. In education, it is critical for us to help our students understand the role of technology as a tool to solve problems and improve experiences. Technology literacy should be a foundation that prepares students to be designers, computational thinkers and problem solvers. To achieve this, students need to learn the electronic tools, methods and apps that help them communicate, collaborate and create powerful content and ideas that bring value to others. Whether it is media creation, app development or programming a sensor, each student needs to develop both a broad and deep understanding of how to leverage technology to solve problems.

7. Don’t wait for permission. Permission can be an enormous roadblock that prevents us from trying new things, taking risks and interfacing with inevitable failure. Permission is the smoke and mirrors that tell us we can’t try until this magical moment of mastery. In school today, students often don’t have a chance to experiment in the unknown, unscripted and undefined.

8. Creativity is a hands-on experience. I cannot emphasize this enough: Students must learn with their hands. They must build things, design things and create things. If students finish your class at the end of the year with only essays, worksheets and exams, then you are missing out on truly making your classroom learning memorable for your students.

9. Put your soul into it. Passion, drive, commitment, determination. However you describe the effort you put into things, there is a certain soul quality that emerges when you truly care about something. If you ask your students tomorrow what they put their soul into, you might be surprised by the answer. You might also be surprised (or not) that the things they put their soul into are not part of school. How we blend those experiences into the classroom, and even more how we create learning experiences that bring the soul to the forefront, will be memorable moments for them. What could learning look like if students put their soul into their work?

10. Stay humble. I once heard an insight that what made Moses humble was not that he thought less of himself, but that he thought more of others. Humility is about looking at ways to engage in the world that put others first.

What does teaching humility look like in our classrooms? How can we shift from learning about others to students engaging in developing their humility through work that directly impacts others? Whether it is students facilitating learning for their peers, helping a friend in need, or creating a social entrepreneurial venture, we owe it to our students to let them build this character trait early on so they can be a positive contributor to society.

Whether we start small (highly recommended) or go all in, the process of building creative capacity is within the reach of everyone, teachers, students and administration alike. What’s important is that we are open to experimenting and exploring what other opportunities can be part of classroom teaching and learning. These 10 principles stand alone and can be built up alone, but together they synthesize the capacity to solve problems and engage in experiences that cannot just positively impact your students but empower them to positively impact the world around them.

Creating a New School

Tell us your personal journey that led you to create your school.

I was educated in a very traditional, Orthodox setting from kindergarten until I graduated high school. (Despite what my friends and kids assert, at no point in my schooling did I attend cheder.) I was exposed to traditional texts, values and thought, as well as traditional teaching practices. I did well in school, but as the years went by, I grew increasingly ill at ease. I eventually managed to articulate what it was that bothered me in a question. (How very talmudic!) If Jewish tradition was as rich and profound as my rabbis claimed it was, why was my experience of it so flat, trite and superficial?

I wouldn’t say I went on to become a Jewish educator out of spite, but, if we’re being honest, I probably did. Ever since I began teaching and learning in Jewish settings, it has been my mission and goal to create opportunities for Jews to experience their history, texts, values and ideas in a more open, direct and transparent way. You cannot hide behind blanket statements like “Judaism says…” or “The Talmud says…”. You have to bring receipts.

I taught in supplementary schools in synagogue basements. I ran classes at Ramah when kids were thinking about anything but Hebrew as a language. I taught preteens and teens in day schools, and led them on summer trips across Europe and Israel. I learned alongside adults as they explored questions of history and memory. I lectured online in university seminars. Somewhere in there, I honed my own thinking about our tradition, professionalized and earned degrees. I also spent a lot time in Jewish kitchens trying to answer the question: What can Jewish educators learn about teaching from cooks and chefs? I wrote books. I started a podcast.

In 2011, Frank Samuels and Sholom Eisenstat invited me to join a conversation about how Jewish education could be better. It was not a formal symposium, just three educators talking over coffee and pistachios. We marveled at what technology could do today that it couldn’t do five years earlier, and why Jewish classrooms were falling behind. We soon realized that talk is good, but like Rabbi Tarfon and the elders stated, it is a necessary precursor to action (Kiddushin 40b).

And, so, after much thinking and talking, we launched ADRABA in September 2018.

Describe the new school.

ADRABA is a blended-learning high school, designed from the ground up to leverage technology to enhance learning in every subject—especially Jewish learning. Blended learning, defined simply, involves teachers using technology to personalize the student’s learning experience.

With blended learning, learning can happen anytime, anyplace and anywhere. Thus, we can structure the day differently. No more bells. No more cemetery seating. No more paper-and-pencil assessments.

ADRABA is Jewish high school, reimagined.

Talk about the school’s innovative features.

Almost every aspect of ADRABA is innovative! When we started the process of designing the school, we took nothing as a given when it came to the learner and meeting her needs. We wanted the learning experience at ADRABA to mirror how a person learns in the world. We gleaned lessons from our own experience as teachers. We talked to teens about how they learn best and how they use technology. All this anecdotal and research data influenced how we designed curriculum, learning goals and how we structure our face-to-face interactions. And as we, too, are human, we take pride in the fact that we, as a school, are learning, too. We will be assessing our practices, policies and processes along with the members of our kehillah. We will try new things. We will surely fail. And, most importantly, we will learn from our mistakes.

What model(s) inspired the design of your school?

Whereas my inspiration comes from theory, Sholom was inspired by experience in the classroom, specifically his years as a teacher in the CyberArts program (cyberarts.ca). One project in particular stands out, even decades later. Some of his students attended the Youth Summit during the 1998 meeting of the G8. While everyone helped to prepare the position papers, the kids who remained in Toronto formed research teams to support their peers in London. He remembers going to student’s house in the middle of the night to watch the sessions.

A question came up on the floor, and a request for information was passed from the kids in the room to the kids in Toronto. The Toronto research team quickly pulled together the research and sent it back to London. Everyone then watched as the note from the Toronto team was passed to the members at the conference table in real time. The kids were interviewed by the CBC, and one was asked about what she learned. She replied, “I learned that there are no limits.” Sholom recounts that his lesson was the same. There are no limits to what competent and well-supported teachers can do with motivated and engaged high school kids and the right tools.

How did you determine that there was a need for your school within your community?

Toronto has a historically robust Jewish ecosystem. Day schools affiliated with all major denominations as well as specific sectors of the Jewish community crisscross the landscape. More than 50 synagogues in the city and its environs provide afternoon and weekend Jewish programming for affiliated children. And yet, when it comes to Jewish high schooling, unaffiliated, Conservative and Reform Jews have only one option. Yet, for many families, that option is either geographically, financially or ideologically “too far.”

Our local Federation tells us that 2 in 3 Jewish Grade 8 students do not continue with Jewish learning in Grade 9. Couple that with the usual drop in synagogue affiliation post-bat and bar mitzvah, and you have what is arguably a crisis in Jewish communal viability.

One would think that, under these circumstances, the last thing Toronto needs is another school… but many parents have told us that if there had been another option when they were high-school age, they might have chosen differently. ADRABA, by its very design, is the alternative. And we are committed to galvanizing cohorts of literate Jews into action.

Imagine where we would be as a society if a vast majority of our citizens stopped learning math, science or civics at age 14. Who would make the next breakthrough in medicine or robotics? Who would design the next, better processor? Who would represent us capably and properly in city council or parliament? If not us, then who?

How then can we expect our community to continue in the 22nd century if there are no literate, engaged Jews to assume the mantle of leadership and involvement? Can we do it with only a 14-year-old’s understanding of our centuries’ old tradition?

We can do better.

Whom are you looking to bring on as teachers? Have you been successful so far?

Because of our unconventional and flexible schedule, as well as being located in Canada’s biggest Jewish community, we have access to a bullpen of educators that are both erudite and engaging. We are regularly approached in line at the coffee shop and via email by teachers from a wide range of disciplines and backgrounds curious about ADRABA. We have secured staff for 2019, and will surely expand the roster in 2020.

How do you recruit for a school that exists only on paper?

We are a school built on an idea: “Blended Jewish.” Our challenge has been finding learners (and their parents) who are as captivated by the idea as we are.

Speaking with hundreds of parents and peers over coffee, we acknowledged our newness, our untestedness, but also our cutting-edgeness and over 80 years of experience in the Jewish classroom, multiple degrees and awards, etc. I also was reminded of one of the more pressing lessons I learned from my research: As much as people love to try new things, they are as terrified (if not more) by newness.

ADRABA is new. But, as Rabbi Nachman of Breslav reminded us, the essence is not to be afraid.

Explain how you’ve gone about finding board members for your new venture.

ADRABA was designed not only to be a 21st century school, but a school that looks and thinks like its kehillah. As such, the founders made a concerted effort to recruit a board that reflects the diversity of Toronto’s Jewish community. When the founders and the board gather to discuss ADRABA matters, we have an equal number of men and women around the table. We have practitioners of Reform, Conservative and Orthodox Judaism, men who wear kippot and men who do not. We have Ashkenazim, Mizrahim and Jews of color. We have Israeli expats and rooted Canadians. We speak from a variety of perspectives, but we all share the same goal: creating opportunities for Jewish teens to become literate and engaged in the kehillah.

What has most surprised you during this adventure of building a new school?

I was surprised by how, from a bureaucratic perspective, it takes so little to open a school in the province of Ontario.

I used to think of schools as edifices built by great men in stovetop hats that would withstand the passage of centuries—or, alternatively, as massive warehouses that churn out workers for the factories.

Schools, I realized, are neither. They are a site of learning built by people, where kids and teachers come together to ask questions and explore answers. Or at least, that’s what they should be.

What advice would you offer to someone else contemplating starting a school?

As much as I’ve gone on at length in response to earlier questions, I will be brief here because I hate to give advice. So, if I must, I will repurpose a shoe company slogan, and say: Just do it.

We need as many literate Jews as possible, and as good as Sefaria, My Jewish Learning and Wikipedia are, googling Jewish stuff does not a literate Jew make. And, sadly, legacy institutions are either too expensive or too slow to change. We need more Jewish learning places, not less. We need more passionate, literate Jewish educators to help make more literate Jews. We cannot cut corners or rest on laurels or hope inertia keeps moving us forward. If we’re to survive and thrive into the 22nd century, we need schools with bold visions to help us along. And everyone needs to pitch in.

Kvod Habriyot: How Multiculturalism can Transform Jewish Day Schools

A quest for new models that address the evolving needs and priorities among Jews, especially millennials, is a challenge for established institutions like day schools. The Lippman School, a K-8 Jewish day school in Akron, Ohio, offers a compelling approach that addresses education and recruitment. Called Kvod Habriyot, respect for all people as God’s creation, the model has enabled the school to admit students from a variety of religious, ethnic, racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.

The Lippman School has succeeded in increasing its enrollment, allowing the school to thrive financially, socially and educationally for the students and their families. This multicultural approach has led a school embedded within a declining Jewish population to a 70% growth in enrollment, from fewer than 70 students to 110, and a 100% increase in annual tuition income over a nine-year period.