How can relationships help amplify school marketing?

In our science labs and maker spaces, during tefillah and on our sports fields, marketing opportunities abound at Jewish day schools. Illustrations of the joy experienced while learning in a Jewish setting are seemingly endless, making the task of elevating this work simpler yet, simultaneously, more challenging. How can you, the marketing or admissions director (or other lead professional), capture and convey such an abundance of publicity-worthy stories? And when this is not possible, how do you choose among them?

An impactful answer can be found in building the right relationships. Fundamental to developing meaningful school marketing campaigns and distilling meaningful stories is having the right relationships, internally and externally.

Establish “Team Marketing”

In order to best recount the vivid stories that capture the value of your school, internal stakeholders, including teachers, educational leaders and administrators should all consider themselves as part of the extended marketing team. Marketing professionals must forge strong, collaborative relationships and develop the explicit understanding that when everyone is on “Team Marketing,” the school will succeed and thrive.

Make Educators Your Partners

Our most significant newsbreakers and makers are our teachers, and they are always “the room where it happens.” Significant classroom engagements and experiential learning opportunities provide the most powerful marketing stories—and teachers and educators should be the marketing team’s best friends.

Tips

Each year, identify a handful of teachers who can be true partners. They may be aspiring marketers, photographers or excellent storytellers themselves, and they are ready, willing and able to keep you in the loop about important story opportunities. These teachers truly understand that your mission is to tell the world about the work they are doing in their classrooms and the lasting impact they are having on their students.

Work with educational leaders over the summer to create an editorial calendar for covering key academic events, and make special note of those that illustrate the special value of your school and/or the “theme” for the school year. Ensure directors, deans and principals consider you an integral part of their extended team, and ask to be included in regular academic department meetings. Volunteer to present at a staff meeting to share key marketing information and successes.

Develop an internal content hub for sharing photos and stories, and create templates to guide teachers regarding content needed for social media or news stories.

Show appreciation. Be sure to send around monthly thank you notes and call out all of your partners on the educational team.

Cultivate Internal Collaboration

Together, marketing, development and admissions form the triumvirate of Jewish day school advancement. Establishing a symbiotic and collaborative relationship between these teams will help achieve annual recruitment and fundraising goals.

Tips

Band together from the beginning. Coordinate annual plans so that admissions, development and marketing efforts are complementary and synergistic.

Create an annual communications plan that demarcates pivotal events and ensures timely outreach to target audiences.

Ensure all teams are in alignment with the designated annual theme and/or key message(s), and create programming, events and collateral that reinforce that messaging.

Establish monthly meetups to enable knowledge sharing, cooperation and leverage incremental advancement opportunities throughout the year.

Let your colleagues know you value their partnership, and outwardly acknowledge how your teamwork benefits the school. Send an internal memo of recognition and accolades.

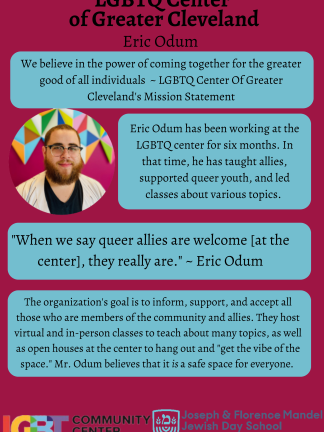

Engage Student Marketers

Today’s students are naturally savvy marketers. Many are already skilled purveyors of their own online presence, and some also have additional experience and expertise in social media marketing, graphic design, videography and photography. Tap into these burgeoning promotional minds and sign them up for “Team Marketing” at your school.

Tips

Look for the helpers. Students who have a natural proclivity for marketing tend to find you. Think creatively about how they could augment your efforts, as well as how you can mentor and guide them.

Create an official Marketing Internship program (during the academic year and over the summer), enabling students to utilize their skills in photography, videography, graphic design, etc., to create social media content for recruitment. Students intuitively know how kids consume content and what they are looking for. Offer samples and templates so students have responsibilities and deliverables; an internship may even count toward chesed / community service or business course requirements.

Lead a business, graphic design or video/photography club, providing a forum for students with interest in and passion for marketing to share their interests and hone their skills. Enlist these students in marketing projects for the school.

Be sure to recognize your students’ efforts and progress. Give students a shoutout for videos they create and other projects they own. Offer to write letters of recommendation for college, employment or other internship programs.

Leverage Parent Advocates

Grateful parents are a school’s most fervent advocates. Developing relationships with these satisfied parents enables them to become excellent promoters as well.

Tips

Create a Marketing Advisory Committee. Select key parent advocates and influencers who can help create a plan of action for spreading the word about your school.

Designate parent supporters as Social Media Ambassadors, who can reshare school social media posts and news and create posts about upcoming admissions and community events.

Harness the power of parent advocacy by creating testimonial videos featuring appreciative parents focusing on the unique benefits of your school, your school community and the value of Jewish day school education.

Thank parent partners for their invaluable contributions. Consider honoring and acknowledging them at an end of year awards ceremony or board meeting.

Developing strong partnerships with educators, administrators, students and parents can yield big results for Jewish day school marketing. Creating and cultivating relationships internally and externally will help enrich promotional content, extend outreach to target audiences, extend your ability to capture and tell meaningful stories, expand outreach efforts, distill key messages and differentiate and market your school. Happy relationship building!