You are a Jewish day school CEO or executive director, working hard to balance revenues and expenses among the myriad other responsibilities you have in your role. You’ve been seeing the headlines about Jewish schools receiving billions of dollars in government funding in various states.

You wonder to yourself, “Wait, there’s massive government money available for Jewish schools? How do we tap into that?”

To answer your first question: Yes, there are federal, state and local government programs that, collectively, inject billions of dollars per year into nonpublic schools. This funding can come in the form of money in your budget, post-hoc reimbursement for eligible expenses, or government-funded services by third-party providers.

To the second question: Explore what exists, decide which programs work your school, apply for the program, and comply with any ongoing or reporting requirements.

Explore

In the United States, all three levels of government—federal, state and local— fund programs for nonpublic schools.

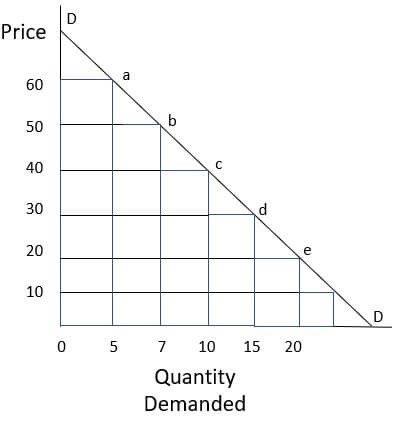

|

Table 1: Overview of Federally Funded Nonpublic School Programs

|

|

Program Name

|

What it Offers

|

Potential Value*

(Ex. School w/ 300 Kids)

|

Run By…

|

Pursue if…

|

|

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

|

Special education services for special needs students

|

Services worth ~$2,000 per special needs student

|

Local school district

|

You enroll students with disabilities.

|

|

Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act

|

Supplemental education services for low-income students

|

Services worth ~$550 per low-income student (varies widely by district)

|

Local school district

|

You enroll many low-income students AND are located in a low-income school district.

|

|

Title II of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act

|

Professional development services for teachers

|

Services worth ~$370 per teacher

|

Local school district

|

You want PD for your staff (every school).

|

|

National School Lunch Program

|

Reimbursement of school lunch and breakfast expenses

|

Meal reimbursements of $130-$1,160 per student per year (depending on family income)

|

State government

|

You enroll many low-income students.

|

|

Nonprofit Security Grant Program

|

Grants for security-related equipment and guards

|

$150K per grant

|

State government

|

Your school has security vulnerabilities.

|

|

*Note: The federal government uses complex formulas to allocate funding for locally administered programs. While these numbers reflect national averages, the amounts per student will vary from district to district.

|

Federal funding can be considerable, but is often highly conditional. Most is reserved for schools with low-income students or students with disabilities. The programs are administered by state or local governments, and each has different eligibility rules and requirements.

State and local funding comes in many forms for many purposes but depends very heavily on where you are located. Many states have generous funding programs, while others do not.

|

Table 2: Overview of State-Funded Nonpublic School Programs

|

|

Program Type

|

Benefit

|

Potential Value

(all vary widely by state)

|

Example States†

(non-exhaustive list)

|

|

Scholarships/Vouchers/ Education Savings Accounts

|

Tuition help for eligible families (eligibility often based on income)

|

$1K-$10K per eligible student

|

AZ, FL, GA, IL, MD*, NV, OH, PA

|

|

Security Funding

|

Reimbursement/grants for security upgrades and/or personnel

|

$120–$250 per student

$50K–$100K per grant

|

CA, CT, FL, MD, NJ, NY, OH, PA

|

|

Mandated Services Reimbursement

|

Reimbursement for state-required activities and services

|

$300-$1,200 per student, depending on school and state

|

NY, OH

|

|

Nursing Funding

|

School nurse hours from district nurses or third-party vendors.

|

$112, but varies per student**

|

NJ, NY, PA

|

|

STEM Teacher Programs

|

State funding for highly-qualified STEM teachers in nonpublic schools

|

$10K–$18K per eligible teacher

|

NJ, NY

|

|

Textbooks, Technology

|

Textbooks and IT equipment supplied and owned by the district

|

$42–$155 per student

|

MD, NJ, NY, PA

|

|

*Note: MD’s BOOST scholarship program is not currently accepting new students.

**In NY and PA, school health services are state-mandated but supplied and funded by local districts.

†Only the 15 states with the highest Jewish day school enrollment totals were considered for this table.

|

In general, there are fewer locally funded programs for nonpublic schools than state or federal programs. Local governments simply have smaller budgets. However, some local governments—especially larger jurisdictions, like New York City—offer substantial funding to nonpublic schools, particularly in free preschooling.

Practically, how do you determine what government funding streams are available to you?

First, see the tables above for an inexhaustive list of federal and state programs that exist in the states with large Jewish day school populations. These can help you see which types of funding are relevant for your school.

Second, visit your state and local government websites. Most have a section for nonpublic schools outlining what’s available and how to apply.

Third, be in touch with your peers in other local Jewish day schools. Compare notes to make sure you are all getting every source of state funding available.

Finally, reach out to your local Jewish day school government advocacy groups. Teach Coalition operates in five states—New York, New Jersey, Florida, Pennsylvania and Maryland—and you can find us online at TeachCoalition.org. Your local Agudath Israel office and Jewish Community Relations Council are also knowledgeable about these programs.

Decide

Every government program has rules regarding who can get the funding, how it can be used and how it can be accessed. These rules may disqualify your school from participating, impose a significant burden on applying for the program, or substantially limit the benefits to your school and students.

You need to decide which programs are worth the effort for your school to apply and comply.

In general, federal programs require significant effort to access, but are well worth the effort if your school and students meet certain criteria. If you have a large number of low-income students or students with disabilities, or you have serious security vulnerabilities, then the benefits can be substantial. Note, the federal programs generally come in the form of reimbursements (National School Lunch Program, Nonprofit Security Grant Program) or services (IDEA, Title I, Title II), so they won’t put new money into your budget.

State and local programs vary widely. In states with scholarships or vouchers, you just need to make sure your school meets the basic eligibility requirements (nearly all Jewish schools do) and can handle the reporting requirements; the parents themselves bear the burden of actually applying. This is generally a no-brainer.

Programs for security improvements, mandated services reimbursement, nursing services, textbooks and STEM teacher programs involve more substantial paperwork. However, since most schools are eligible and the funding is significant, it’s usually worth the administrative burden.

Preschool funding programs around the country are trickier. Many come with a host of space, curriculum and hours requirements; review these closely to see if it makes sense for your school to participate.

Apply

Nearly every program at every level has a webpage with instructions on how to apply. For federally funded IDEA and Title programs, school districts are required by law to reach out proactively and invite you to participate (though not all districts do this diligently).

Simply find the right instructions and application documents and follow them closely. Every government has program staff who can answer your questions. Teach Coalition and other advocacy groups generally have staff available to help if you run into any trouble.

If you aren’t sure what to do, or even where to start, then reach out for help early in the process. For the extremely complex National School Lunch Program, many schools rely on third-party firms that employ experts with decades of experience to handle the application, compliance and reporting aspects of the program.

One important point is to double check every word of every application for compliance with the application instructions and program requirements. Leaving out key information or supporting documentation—most applications have some sort of required attachments—can result in your application being denied.

Finally, apply early. Waiting until the week of the deadline to begin reviewing and completing the application invites all kinds of risks: not getting it done in time, encountering questions you don’t know how to answer, or learning of required documents that take more than a week to track down.

Comply

Most programs have requirements for how the funding can be used, how the services are received or what information must be reported to the government.

Programs that provide government-funded services—IDEA, the Title programs, the New Jersey STEM teacher program and school nurse programs—generally require close and ongoing coordination with your local school district.

Programs that provide government-supplied equipment—certain state security programs, textbook programs and technology programs—generally maintain government ownership of the goods and may require annual inventory or other reporting requirements.

Programs that cover tuition costs—scholarship, vouchers and preschool programs—may require financial audits or reporting to ensure the money is not misused. Such reporting can be quite onerous, depending on the state and program.

Programs that provide reimbursements—most security grant programs, mandated services reimbursement programs and the New York STEM teacher program—generally have no reporting requirements after the reimbursement application is approved by the state. (Note: For security grant programs, there is usually a one- to two-year period between grant award, completion of the approved security project and final reimbursement by the state. During this period, these programs often have ongoing quarterly reporting requirements.)

Whatever compliance or reporting requirements are attached to a program, it’s important to follow them carefully. Some programs impose penalties on schools that fail to meet the requirements, such as being barred from future funding, and may even claw back the funding.

Advocate

Government funding can be a large revenue stream for Jewish day schools. In states with large school choice programs, these programs can contribute to upwards of 30% of a school’s budget. Even in other states, combined state and federal programs can reach 5–15% of a school’s budget, for the right school. This is aside from the government-funded services that may be available to your students.

Teach Coalition’s state divisions in New York, New Jersey, Florida, Pennsylvania and Maryland are advocating nonstop to increase government funding for our schools. Our grassroots advocacy has dramatically increased nonpublic school funding in the states where we operate, from less than $400 million in state funding in 2012 to about $2.5 billion in 2022.

Our successful advocacy relies heavily on participation by Jewish schools, students and their parents to influence politicians and keep moving the needle on government funding.

As a school administrator, we urge you not only to maximize your school’s government funding, but also to join us in advocating for increased government funding across the board.